The Hoxton Horror

Readers of previous articles in the Victorian Unsolved series will have a pretty fair picture of Victorian London in their minds by now. While today’s popular culture gives us an image of Downton Abbey and a world very removed from our own, the truth is rather different. People lived rather as they do now, with the same motivations and drives that permeate our own lives. They worried about their wages, were exploited by their bosses, and enjoyed a drink. Their sex lives were also a world away from being embarrassed by a naked table leg.

The city was changing. Development from Britain’s farming past into its industrial future had created a chaotic scene as the city’s slums filled with factory workers, the centre of the empire showing the vast disparity between rich and poor. This empire of the few is not unusual, and yet perhaps at no time has the gap between the richest and poorest in society been so obvious. Places such as Whitechapel would become notorious for their lawlessness, as desperation and poverty forced the poor into lodging houses and even the workhouse, many turning to drink to shut out the horror of the “dark satanic mills” that now blighted their lives.

With this growing lethal combination of poverty, alcohol, and desperation, all coupled with misunderstood mental health problems and the shock of a rapidly transforming society, it’s perhaps no wonder that violence became an almost daily occurrence in London. However, one bright summer’s day in Hoxton would perhaps show a new level of brutality, and the sun would offer no respite against the carnage for which London was becoming known.

The Hoxton Mystery

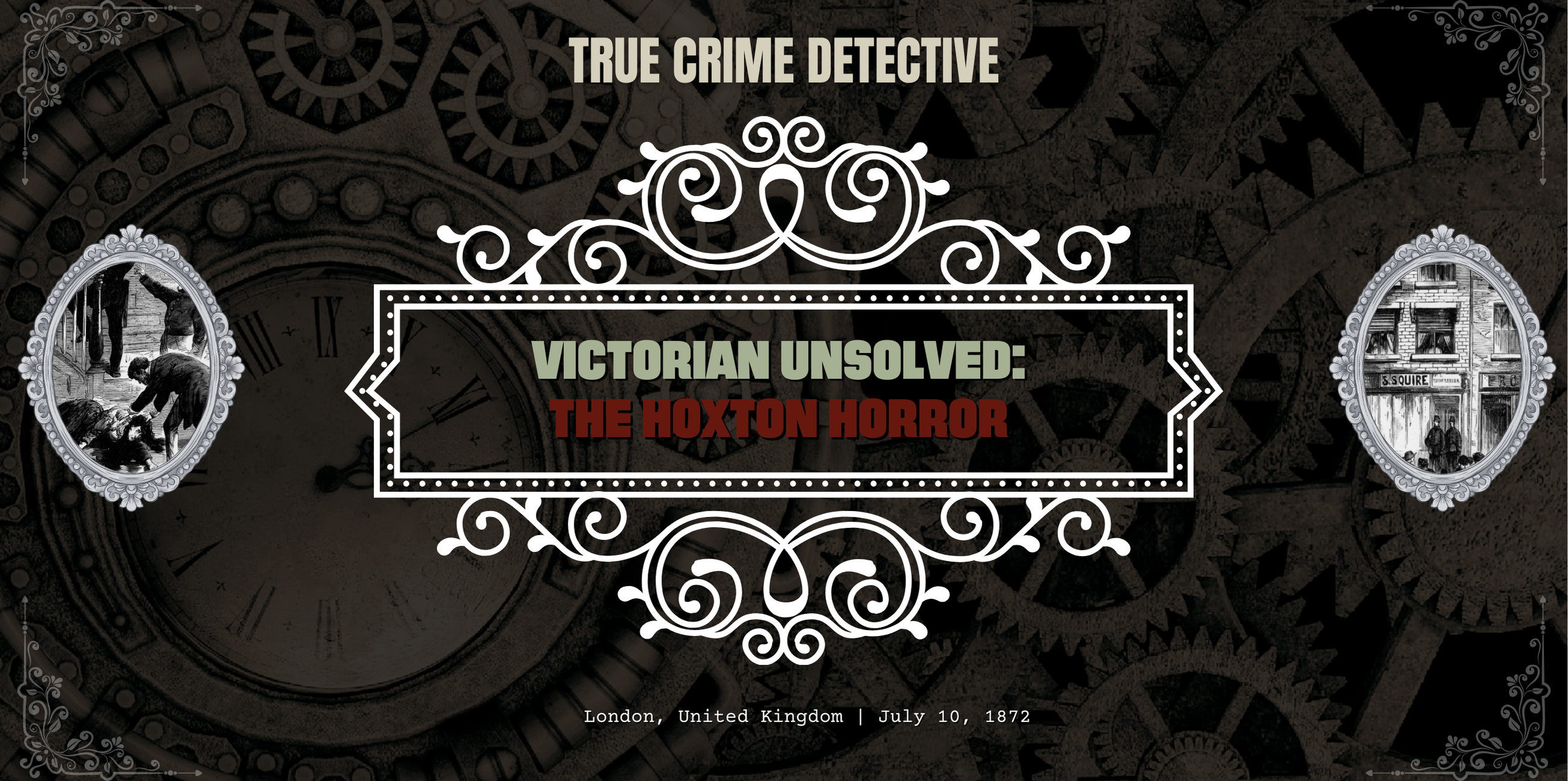

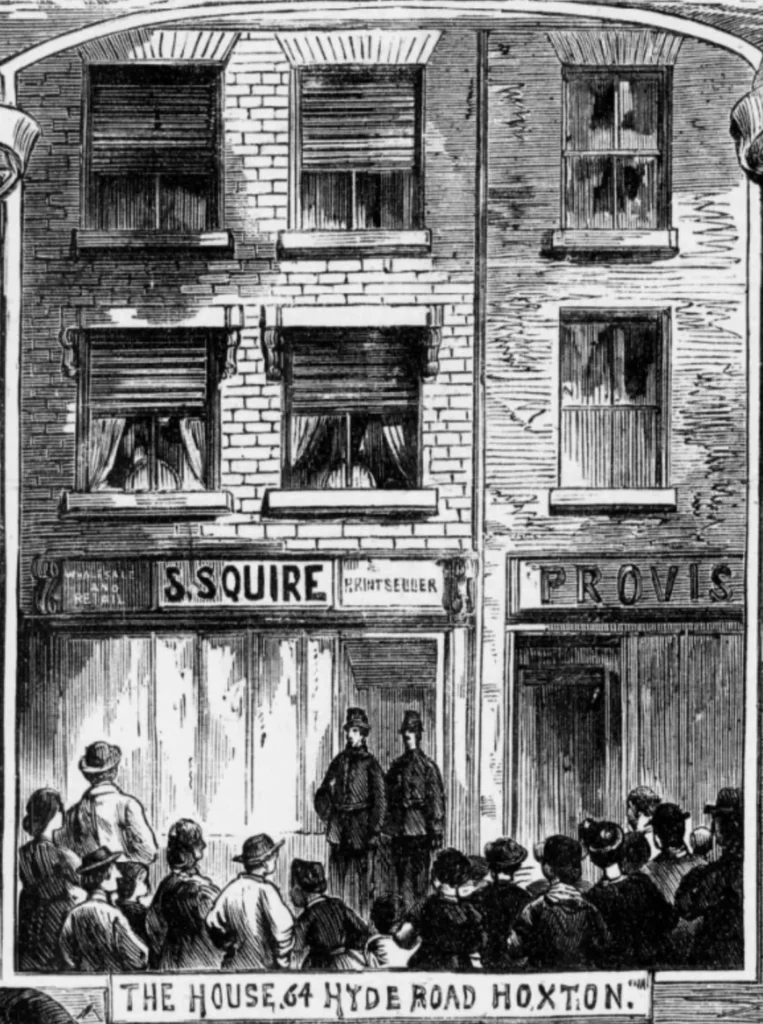

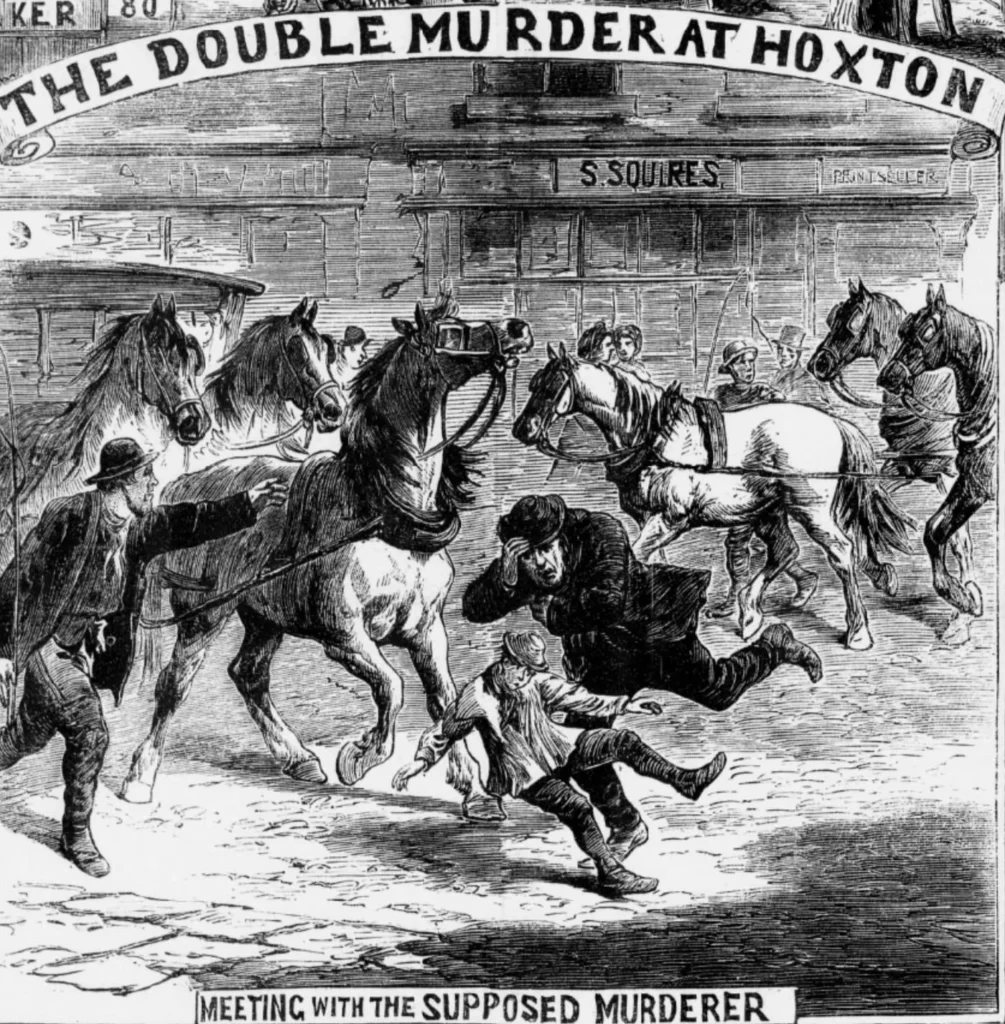

It was July 10, 1872, and the place was 46 Hyde Road. Here, Sarah Squires, 77, and her daughter Christiana Squires, 36, ran a stationary business, with “S. Squires, Wholesale Stationer, Printseller. The Trade Supplied” proudly painted above the door. As is often the case, the victims’ ages are wildly varied in press reports, and some accounts claim Sarah was 73 or 76 and her daughter possibly 38 or as old as 48, though via census reports, the above would appear correct.

The place was, in many ways, the stereotypical image of a Victorian street. It was by no means wealthy, looking dusty and faded, while placards of the “East London Theatre” and the “Cambridge Music Hall” adorned a butcher’s shop. However, there was every amenity you might need, including a greengrocer and pub, The Flint House. The two women lived alone at number 46, with Christina being a widow and owning the house and shop, having taken over following the death of her husband.

Sarah Squires had been married twice, first to tobacconist William Pritchard. The two had a son, Edwin, and two daughters, Sarah and Jemima. After William’s death, she married John Squires, a print seller. This marriage produced more children, Christina and Francis. The women were said to have lived a somewhat solitary and independent life, having few visitors and often refusing assistance in their business or domestic affairs. This perhaps allowed rumours about their business to spread, with the word in the local area suggesting the two had a decent amount of wealth between them, which was hidden in their home.

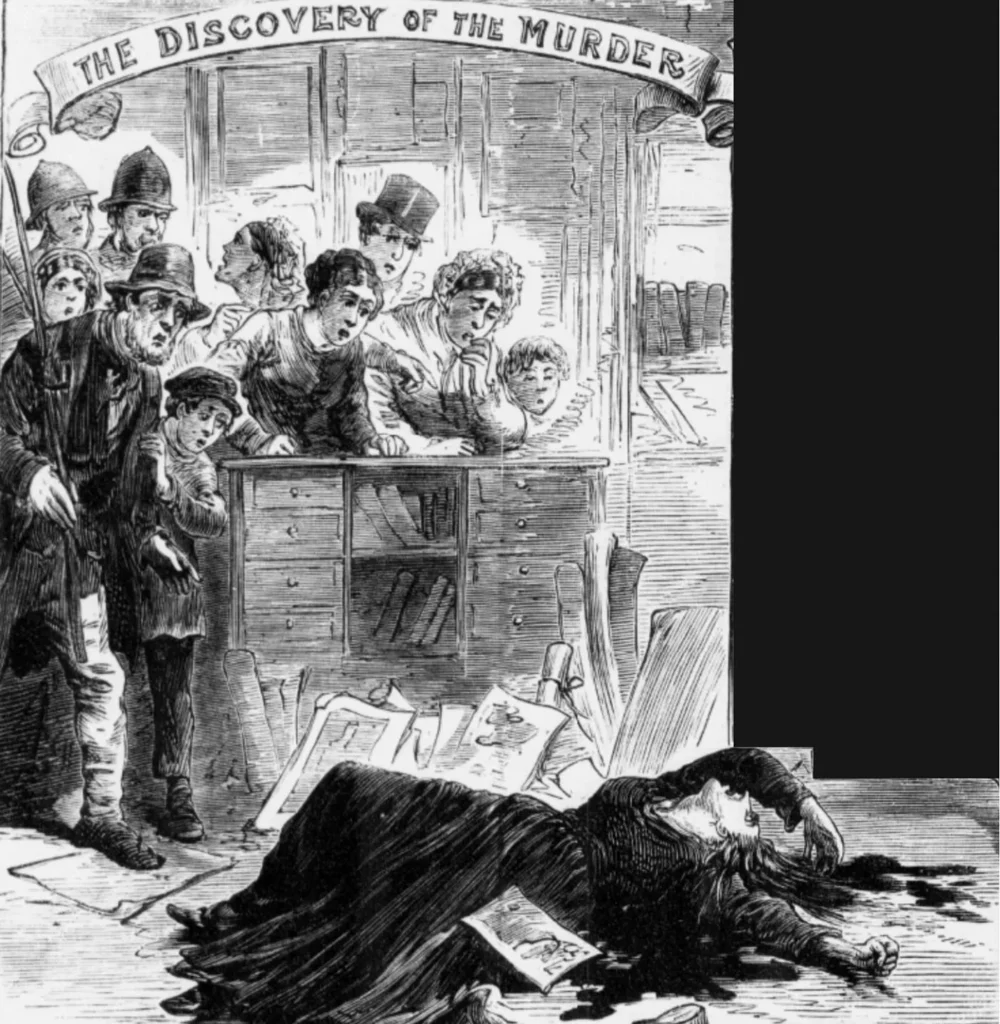

The day started just like any other, with Sarah opening the shutters early and both women being regularly seen throughout the morning, with the last confirmed sighting of Sarah being at 11:20 am. However, around 1:10 pm, a young boy named Archibald Trower entered the shop to buy paper and some envelopes. Despite seeing blood on the counter, he found the shop empty and left when nobody answered his call. Not long afterwards, another boy, William Eyre, entered the shop on an errand to buy stationary or, according to some accounts, buy a newspaper. However, this seems unlikely as the boy would have to have been unaware that the shop didn’t sell newspapers and was a wholesale and print dealership.

Eyre also found the shop empty. He waited a few moments and, when nobody appeared to serve him, began to laze against the counter, resting his arms on it, finding blood and hair splattered on the papers. Eyre quickly ran from the house. Yet again, the press disagreed on the details. Some accounts say he went to a coffee shop next door to raise the alarm, while most instead agree that he ran to Edward Dodd’s the greengrocer directly opposite, fetching his wife, Harriet. In any case, after the owner of whichever shop he alerted confirmed the finding, the police were summoned, and Constable James Kingsley was first on the scene. Sarah and Christina Squires were both dead.

A Scene of Carnage

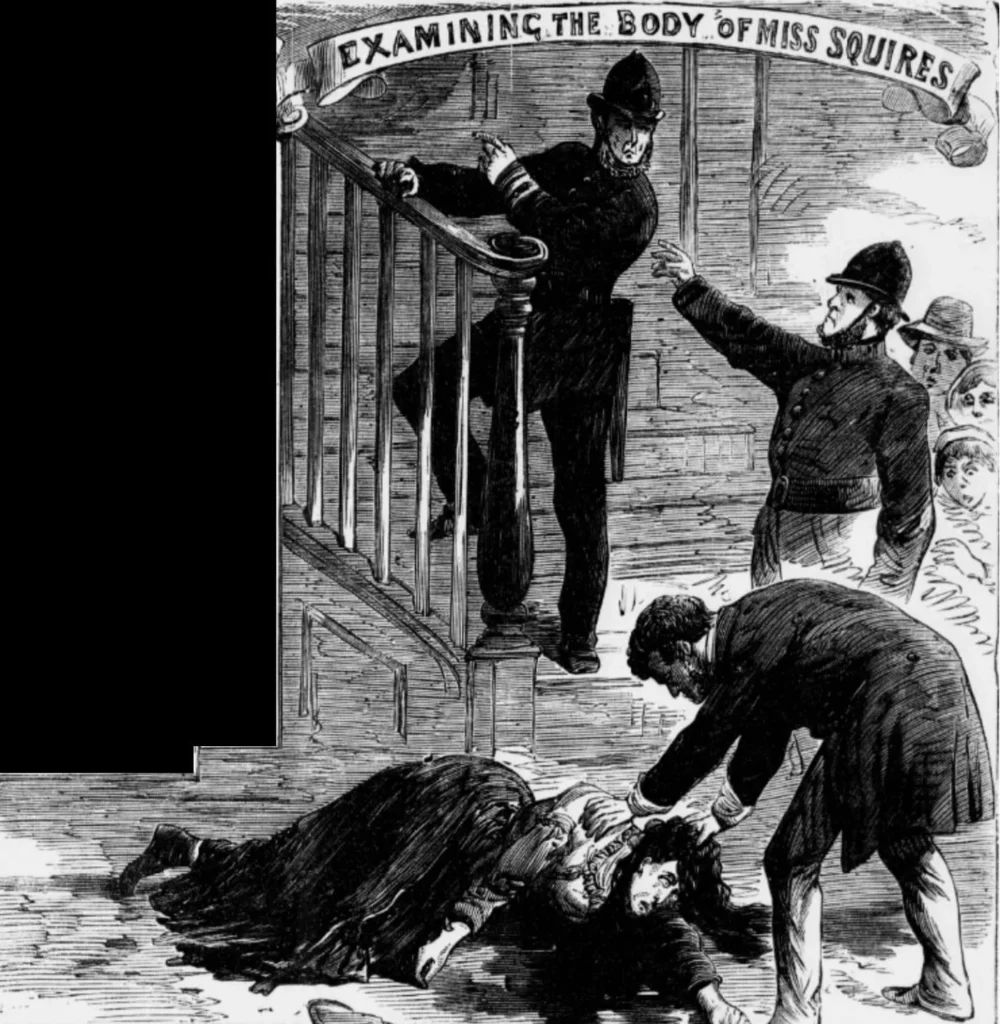

Inspector Ramsay of N Division soon arrived and found nothing but brutality. Sarah Squires was lying behind the counter with her head and face obliterated by a severe battering, blood splatter covering nearby surfaces. Her skull had been smashed, and her left ear almost severed from seven severe blows. Christina Squires had suffered the same fate, being found in a corridor connected to the shop parlour with five blows to her head, her legs facing toward the shop. Police believed the crime had been committed with a blunt instrument such as a hammer or an iron bar. The victims had been mercilessly beaten even after they were dead.

The till had been robbed, and everything in the shop had been ransacked with strength and determination. Drawers had been prised open, and their contents were strewn around. Cupboards were opened and searched, and a large clock which had stood in the parlour had been knocked down and moved, stopping at noon and giving a possible time for the killings. Interestingly, the clock had been opened and removed, exposing the workings as though the killer had looked inside for something. The fact that the killings took place around this time was backed up by the fact that there was a saucepan on the hob containing a dumpling, indicating that preparations for lunch were underway.

Meanwhile, underneath a sofa, police found a will that Sarah had secreted inside a paper bag. There was no evidence, however, that this was what the killer was searching for. Equally, the women’s savings were found underneath a bed alongside bank deposit notes, meaning that if robbery was the motive, the killer failed to look in one of the most common places for hiding money.

Police immediately suspected the motive was money, going off the evidence at the scene. Yet, the ferocity of the murders made it stand out as something different. The culprit obviously had some strength, and restraining two women alone in their shop would have been little problem. Yet, extreme violence was chosen, with police believing the mother, Sarah, was attacked first, and then Christina was struck down as she tried to render assistance.

The killings being carried out by a lunatic may have been one solution, and police may have momentarily thought they’d got lucky when it was revealed that Sarah’s son and Christina’s half-brother, Francis Pritchard, was severely mentally ill. A witness could place him at 46 Hyde Road on the morning of the murders. Francis was known to be a drunk, often in trouble with the law, frequently found in the workhouse and at one point had been in the Colney Hatch Asylum that would one day be home to Severin Bastendorff and Jack the Ripper suspects Aaron Kosminski and David Cohen.

It was revealed to police that Francis may have had a grudge against the rest of his family, with Sarah Squires being forced to turn her son out of the house through his drunkenness, cutting him off from his means of finance. However, further investigations revealed that the man had been committed to the lunatic ward at the Shoreditch Workhouse all day and was working in the kitchens. The witness was therefore mistaken, but that hardly stopped the local gossip. Meanwhile, the other son, Edwin Pritchard, was a musician and away in Brentford at the time, eliminating him from enquiries. Christina’s son, George, 17, was also similarly eliminated when his alibi of being at the barbers where he worked was proven.

Subsequent investigations revealed that the murder weapon had been a plasterer’s hammer, something of an interesting parallel to our previous case, the Burton Crescent Mystery, where, at one point, a plaster drunkenly confessed to beating Rachel Samuel to death in 1878. At the autopsy, grey hairs were found on Christina’s hand, perhaps from the beard of her killer.

The case was almost cold from the very beginning, with police having absolutely nothing to go on. The killer left nothing at the scene, and despite being a somewhat busy street, he had seemingly carried out two murders and a robbery with impunity, with no witnesses having much of anything to tell. There was a drayman, perhaps delivering beer to the pub, who saw a man running from number 46 around the time of the killings, and police heard that on the Saturday before, there had been an attempted burglary at the shop with holes being made in the back door. Sarah had become aware of what was happening, and a constable was alerted. As the police rushed to the house, breaking glass was heard as one of the men in the garden had thrown a brick through a rear bedroom window. Sarah had also told a friend, Caroline Richards, that a tree branch had been broken by a cat, with the possibility being that the burglars had done this.

Some believed the same people likely carried out both events. However, this seems like something of a leap. Police found that the holes in the back door had been bored in, and breaking the window wasn’t a random act of violence; rather, it had been done to send an alarm to accomplices working at the door. The careful burglar attempting to enter covertly seems a different kind of man to one who walks through the front door and beats two women to death in a horrific fashion before ransacking the premises.

“The well-known stationer’s store stands out now like a rebuke to the rest; the name of the dead stares at you from the doorway as if the letters were traced in blood; the blinds are closed against the daylight; the dumb windows seem still to shut in the scene of blood; the whole house pleads to the passer-by for vengeance.” — The Gentleman’s Magazine, 1872

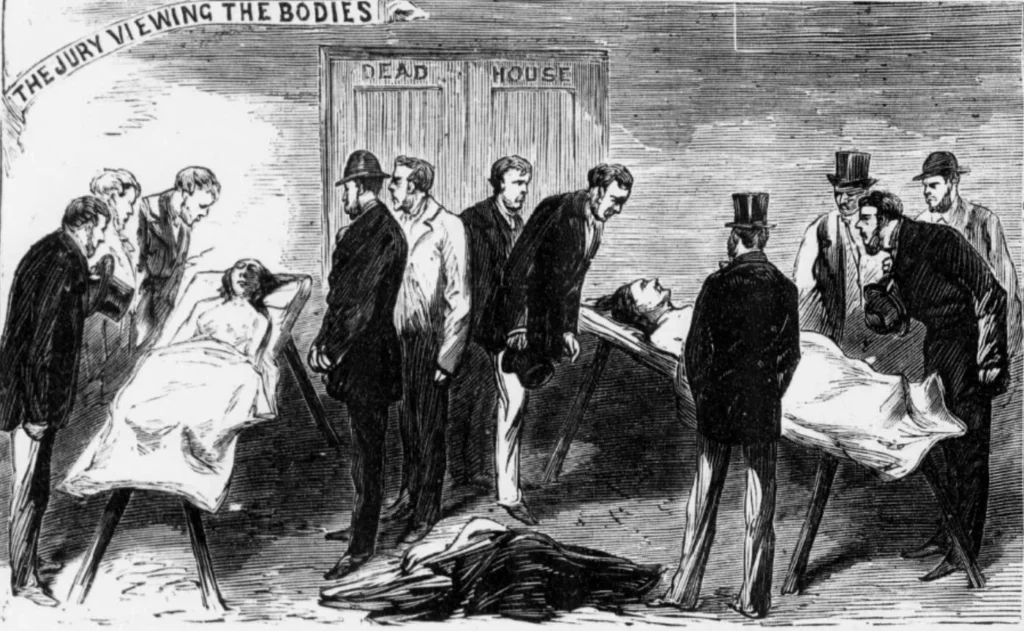

Inquest and Tragedy

The subsequent inquest into the deaths of Sarah and Christia got underway at Shoreditch Workhouse, and Caroline Richards was called first. Caroline resided at 30 Newport Street on the end of Hyde Road and said she heard a cry of “murder” around noon, but as drunkenness was prevalent in the area and she’d regularly heard such cries of distress, she thought nothing of it.

Henry Inall, a butcher, said he had called on the house around 11 am on the day of the murder, and all was well. He made conversation with Sarah Squires, and she brought up the attempted burglary the previous Saturday. Sarah showed him the holes in the back door and how she had papered over them. Inall reported that Sarah told him, “If they were to get in here, they would not get anything; because when I go into the City, I take my money and leave it there.”

George Squires was next to the stand. George stated that he used to live with the two women at 46 Hyde Road, but had left two tears ago. However, George continued to visit and was last at the house and shop three weeks previous. He had little more to add except noting some of the men who frequented the shop, including “York,” a seafarer and Niblett, a stonemason courting his sister. York was found in Scarborough, and Niblett revealed that he had split up from Christina four years ago after discovering she’d been seeing somebody else.

The inquest was going nowhere fast. A carman, Charles Wallen, noticed two men in the street but little more, and the inquest was subsequently adjourned. However, before it could resume, further tragedy would strike the Squires family as another daughter, Jemima Squires, aged 42, committed suicide on July 20.

Jemima, who was Sarah’s eldest daughter, had once worked alongside the two women at 46 Hyde Road but now worked as a charwoman (cleaner). She had once been married to a man named Nottman and had two children with him. The two had separated some years before. Jemima was now deathly afraid of being called to the inquest and having her personal life put before the public, particularly as there was said to have been tension in the family. Whether this was because they’d disapproved of her marriage isn’t known, but her fears led to her cutting her throat. Despite malicious rumours that she’d been involved in the Hyde Road killings, police ascertained that she had an alibi and Jemima had suffered from what we would today understand as depression for many years.

The mood when the inquest resumed was likely to be sombre, but things began to improve in terms of information. James Jones, 17, worked as a carman’s assistant and walked down Hyde Road around the time of the murder alongside a wagon. Jones observed another wagon coming in the opposite direction, and that a man had ran into the road, being promptly knocked to the ground by the lead horse. He quickly got to his feet and curiously hid his face as he ran away. He was pale with a dark beard and wore a hat with a wide brim. However, the description did not mention blood stains on his skin or clothing.

Next was a glazer, Charles Henry Hasler, 21, who revealed that he had called on the house to fix the broken window on the Monday before the killings. While there, Sarah Squires told him she knew the culprits.

“It was done with a piece of brick. It was the thieves, and I suspect we shall all be murdered,” Squires had reportedly said. “The worst of it is, it is our neighbours. I know them very well. It is in that street.”

Sarah had indicated Gopsall-street, adding that she knew who the culprits were.

“One ran from my house, and one was in the yard at the other side of the wall, and another stood on the wall, making three in all,” she had added. “The man in the yard threw the piece of brick to the man on the wall, who threw it through the window. We shall be all murdered, sure as I am alive.”

Hasler told of how he took the window away before returning with it half an hour later, with Squires repeatedly stating that she was concerned about being murdered but didn’t want to tell the police. It was revelatory evidence, and potential suspects were no in the frame if the events were linked. Indeed, many believed that the murderer had been local to the area and known the shop well, being familiar with the routines of the victims, and Hasler’s evidence would certainly point toward that. The inquest returned a verdict of wilful murder by persons unknown.

However, despite the claims that individuals on Gopsall Street might have some knowledge of the killings, nobody was arrested, and nobody was ever brought to trial, with little evidence for who might have been responsible or what the true motive might have been.

However, there is one footnote in the tale. On August 29, 1888, on the eve of Jack the Ripper’s reign of terror, Thomas Wright, 36, confessed to the double killing. Wright, a chairmaker, drunkenly stated that he had killed both Squires women with a crowbar. His account of the murders pretty much tallied with the facts. However, any initial excitement faded when he was proven to have been at work on the day in question. Wright, who recanted when sober, was arrested for wasting police time and eventually discharged.

Was It a Robbery or Something More Personal?

On the face of things, the double killing in Hoxton is a simple robbery gone wrong. The till was robbed, the house was ransacked, and the killer seemingly searched for something. It was rumoured in the area that there were valuables on the premises. However, the killers failed to find money under a bed, and the savagery of the murders suggests something personal. After all, an armed man would hardly have any trouble subduing two women without resorting to murder, particularly as Sarah Squires was an old woman. However, there was no evidence that anyone had a personal grudge against Sarah and Christina Squires, with nobody in the local area having anything bad to say about them. The theories about Gopsall Street don’t seem to have panned out, eliminating any suggestion that the Squires women may have been silenced.

Still, it’s worth remembering that corpses are useless to most thieves as dead people can’t reveal where valuables might be. Equally, murder at this time was a capital offence, and it would take a truly desperate or unwell individual to take such a risk for the takings of a print shop. With that said, people have been murdered for much less, and it’s more than possible that the culprit could have been suffering from psychosis or be under the influence of drink, explaining the violence without the need for a grudge. However, if that were the case, would the killer have been capable of keeping quiet for so long?

Whether the previously attempted burglary was linked is debatable. It’s quite a change in tactics from house breaking to walking inside in broad daylight and battering people. The man brazenly exiting through the front door and across a somewhat busy street shows little planning, suggesting that the murders may have been spur of the moment.

In any case, the double murder in Hyde Road would never be solved, and the press lamented that the horrific killing seemingly had little effect on Londoners, soon fading into memory and the killer walking free. Was the city becoming desensitised to this violence, they asked? Little could they know what the next quarter of a century would bring, with murders only becoming even more violent and sensationalised. Before the end of the century, London would bear witness to the Torso Killer and, of course, Jack the Ripper.

“This terrible crime has been allowed to drop out of public memory with a calm resignation which does not add to one’s peace of mind… Are we in these days becoming callously accustomed to foul deeds, or is the business of life so much more engrossing than it used to be, that we see criminal after criminal slipping away from justice, without some stirring protest?” — The Gentleman’s Magazine, 1872