The Harley Street Mystery

In many respects, the 19th century is a golden age of crime. It is an era where police methods are only just beginning to develop into what we know them to be today. Photography and fingerprints were nonexistent or in their infancy, and the prospect of DNA was far away. As such, there are a great many crimes that remain unsolved and while the realm of an unsolved crime in the Victorian era is dominated by Jack the Ripper, the darkness exemplified in those killings existed long before Jack’s shadow darkened Whitechapel.

The era was one of fundamental change in British society, with the country transferring from agrarianism to industrialisation, and, as such, the cities began to swell with the poor. Exploited and without the rights we now hold dear, the impoverished of cities such as London were forced to live in absolute squalor. Many turned to drink, others to crime, with prostitution and petty street crime endemic.

It was easy to believe that these faceless masses had been abandoned by British society, their lives worth little. The classism of the age, which some may say still exists today in developed forms, meant that crimes against these working-class communities would never rank as important to police and the establishment as crimes committed against those of a higher social status.

In this atmosphere, we find many of the unsolved cases of the Victorian era. There was the infamous case of the Hoxton Horror, the Thames Torso Killer and the West Ham Vanishings. Indeed, the number of crimes where no justice was found runs into the hundreds. This new series will cover many of these crimes and we begin with a little-known case — the Harley Street Mystery.

The Harley Street Mystery

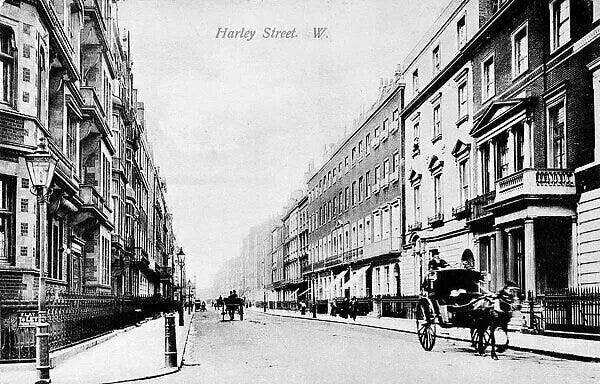

In 2023, we know Harley Street in London to be a centre for private medical care. The street is littered with some of the finest doctors in the country and frequented by the rich and famous seeking whatever treatment they need, quite often plastic surgery. However, this wasn’t always the case, and back in 1880, the street also featured many private houses and other businesses. There were 60 doctors on the street in 1860, growing to 80 by the turn of the century. Today, over 3000 people on the street are employed in the medical profession.

For this reason, many assume the involvement of a medical professional in the Harley Street Mystery. However, this is far from the case and perhaps more a sign of contemporary mistrust in the then developing field of medicine and science. After all, many believed Jack the Ripper must have also been a medical man, which speaks to fears in Victorian Britain that science would lead to the failure of society and morality than any actual truth.

Instead, our tale takes place at the home of a wealthy Jewish merchant, 68-year-old Jacob Quixano Henriques or the noted Henriques family. Henriques had lived in the number 139 Harley Street house for 20 years, and his wealth allowed him several servants. As usual, at the time, the servants worked downstairs, with the master of the house being upstairs. The servants only occupied the house while Henriques was in Britain, with a caretaker and his wife living there when he was abroad. As such, Henriques hired new staff regularly, meaning they were often of a lower standard than expected. He lived at the large property with his wife, Elizabeth, and three adult daughters.

It was in January of 1879 that Henriques was first made aware of an unnatural smell in this cellar space, presuming that it was coming from the drains. With the smell not going away, it would be six months later that Henriques employed a plumber to investigate, and after they’d completed their job, the smell seemed to dissipate.

However, it wouldn’t be long before the smell returned to the cellar, getting stronger and becoming unbearable. So strong was the smell eighteen months later, on June 3, 1880, that the footman of the house alerted the butler, with the two determined to get to the bottom of the mystery. Investigating, the two observed a large iron cistern which stood on four props that were either wooden or made of brick. Beneath this cistern was an open-topped American flour barrel, with the open space filled with old bottles and other refuse.

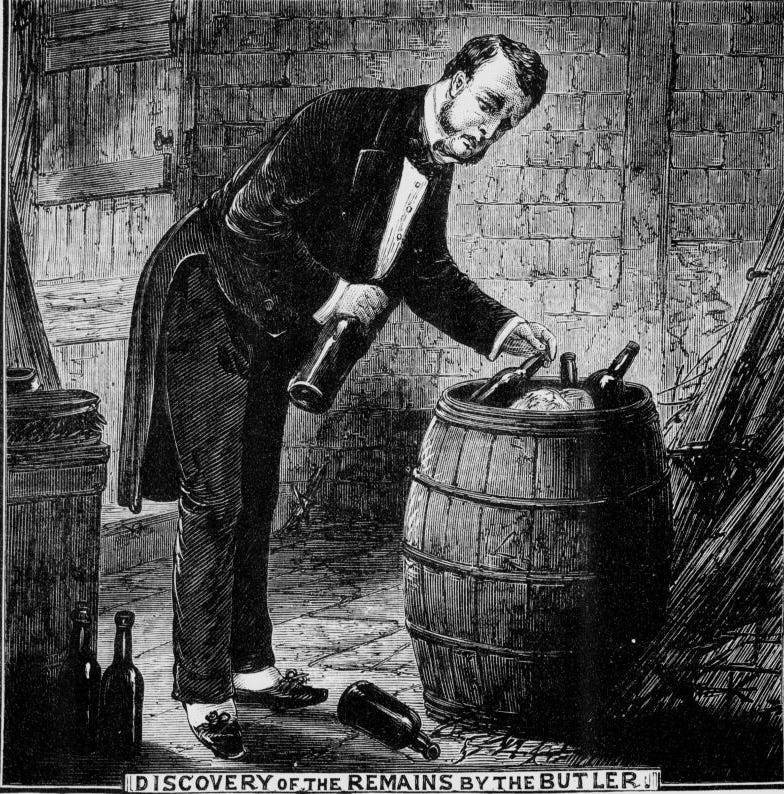

The two men suspected the smell was coming from the area and moved the barrel out from under the cistern, struggling with the unexpected weight. Removing the debris from the top, the butler was startled by what he saw, crying out, “There’s somebody in here!”

The Body In The Barrel

Following the horrific discovery, the butler informed Henriques who told him to fetch the police, who arrived on the scene around noon, led by Inspector Lucas. They were followed swiftly by Mr Bond, an expert from the Home Office. After the bottom end of the barrel had been removed by Lucas to get a better look at the discovery, it could be seen that the partially mummified body had been stuffed inside headfirst, with the knees drawn up into the abdomen to fit the corpse inside. Bond could see the remains of a woman’s head and shoulders thanks to Lucas’ removal of the bottom, with the knees otherwise being the only thing visible when the barrel was upright.

The barrel was completely resealed to preserve the evidence and removed for deeper investigation. While the macabre discovery was on its way to the infirmary at Marylebone Workhouse, police began to investigate the scene. They found little of use in the cellar, with a table knife, pokers, rope, and rags being found, but little that would have been unusual for the location except perhaps the knife.

Once a full autopsy could be performed on June 4th and 6th, several things became clear. The woman’s body was between 30 and 40 years old, and believed to have been poor. The body had been clothed in the remains of a chemise, underwear and stockings that were determined to have been of cheap manufacture. The deceased had dark brown hair, just beginning to go grey, and was small in stature, being 4’9″.

However, there were no means of establishing the victim’s identity as the facial features had been obliterated during decomposition. The body had been in the barrel for between 18 months and two years, the same length of time that the smell had been detected in the cellar. The cause of death was believed to be a single stab wound to the left breast, with the chemise showing blood and a cut above, showing she had likely been in her underwear at the time of death. The knife found at the scene could have been the murder weapon, but no evidence of blood was found on the blade.

The remains were also said to have been covered in chloride of lime, the killer or killers mistakenly believing it would aid decomposition. They presumably hoped that a more decomposed body would hide the victim’s identity. Interestingly, the medical examiner couldn’t eliminate the possibility that the remains had once been buried and covered in the lime before being moved into the barrel. Evidence from the body showed that the woman had once been extensively covered in the substance, with the expected amount having not been found in the barrel. The only lime discovered in the barrel was consistent with transference from the body. Interestingly, police discovered evidence in the cellar that attempts had been made to dig a hole.

Meanwhile, the questioning of witnesses at the scene revealed very little. Jacob Henriques claimed that he knew nothing of the matter, only being able to detail his efforts to eliminate the foul odour. The butler and footman who found the body, John Spendlove and William Tinapp, had been in their jobs over 18 months and were said to be of excellent character while the rest of the servants at the house were female, and little suspicion came upon them.

The Inquest

While the police seemingly had little to go on, the inquest was more revealing, with the witnesses shedding a little more light on the mystery.

Perhaps the key witness at the inquest was Henry Smith, a soldier with the 3rd Infantry. Smith was formerly the butler at 139 Harley Street, having left the service of Jacob Henriques in November of 1878, placing him in the home around the time that body was believed to have been secreted in the barrel. Smith, dismissed for drunkenness, denied all knowledge of the corpse, claiming that he rarely went inside the cellar space but was responsible for locking the gate and it was frequently left unlocked. This was done so the servants could come and go as they pleased and bring people back to the house. While telling of this fact, he revealed he had once caught the footman Tinapp drunk, letting him in at night.

The image below from the Illustrated Police News shows how the gate led to the cellar.

Asked about the attempts to dig a hole in the cellar, Smith confirmed that he ordered the hole dug by workman John Green in August of 1878. Asked why he would want a hole in the cellar, Smith’s response was bizarre, claiming that stale bread was abundant in the house and he wished to bury it. Smith added that the attempt failed as Green came across a layer of concrete underneath the flagstones and unable to proceed. At this time, the barrel was located in the centre of the room. After Smith left service at the house, an item of Jewellery was reported missing. The investigating officer, Inspector King, decided to look underneath the flagstones when he heard the ex-butler had lifted them. To do so, it was the police themselves who moved the barrel underneath the cistern.

Meanwhile, Green would confirm to the inquest that he had undertaken work for Smith but stated that the flagstones had already been removed from the cellar’s floor and that he undertook no digging. Instead, he replaced the stones, not asking Smith why they’d been removed in the first place, with the butler not making any statement about burying bread. While Green was 74 at the time, and his memory must therefore be treated with caution, he didn’t remember seeing the pokers or knife.

These events of August 1878 coincided with the arrival of Tinapp in the household. Tinaapp was German and claimed that the hole in the cellar floor had already had its bricks replaced when he began work. He added that the barrel was already in the cellar and he noticed the smell immediately. Tinapp would go on to state that during his service, he never noticed any excess waste that would require a hole to bury.

The facts surrounding the “stale bread” story was confirmed by Spendlove and another witness, Mrs Jewry, who served as a cook between 1874 and 1879. While Victorian sanitation and trash collection were certainly not up to modern standards, there would have been no problem with the dustman taking any excess waste, as Jewry emphatically stated.

The verdict of the inquest was the wilful murder of an unknown person, with the decision not naming a suspect despite being empowered to do so. The police were heavily criticised for their actions at the crime scene, with the opening of the barrel coming in for particular scorn. Some believed that clues were undoubtedly lost. Following the conclusion, police investigations continued for some time, but they could never build a case, meaning the Harley Street Mystery went unsolved.

The Butler Did It?

There were several theories in the case, including the astonishing idea that it may have been a case of suicide, given the woman had been stabbed in her left breast. If one of the servants had smuggled a woman into the house who had killed herself, it might not be beyond the realms of possibility if he feared for his job or that he might be accused of murder. However, it seems far more likely that police were dealing with a case of murder and that Henry Smith would have been considered the prime suspect.

Smith, who was sacked for drunkenness and at least suspected of theft at one point, was in the house at the time and eager to insist to the inquest that the gate was frequently unlocked. However, his inexplicable actions regarding the cellar point to his guilt, particularly his almost absurdist claims about stale bread. Could it be that Smith himself smuggled a woman into the Harley Street house, perhaps a prostitute, and stabbed her to death in a moment of drunken anger? Panicked, Smith pulled up the flagstones in the cellar, hoping to bury the body beneath. He was foiled when he encountered concrete and required the assistance of Green to replace the stones before too many questions were asked. The butler then needed a fresh place to hide the body, settling on the barrel.

While this would seem to be the obvious solution, it fails to explain the belief of the pathologist that the body had once been buried and covered in chloride of lime. Equally, the theory doesn’t explain why Smith was seemingly happy to leave the body in a place where it would surely eventually be discovered. However, it may have been the case that he was sacked before he could devise an alternative.

Whether the culprit was Smith or not, somebody got away with murder. While the Harley Street mystery story has its unique points, it also has sad similarities with crimes that stand out through the Victorian age, such as women being the victims of extreme violence and murder victims in poverty vanishing unmissed and found without a name.