The Cellar Killings: The Uncaught Serial Killer That Stalked Helsinki

Throughout the late 1970s and into the 1980s, a rapist and serial killer stalked the streets of Helsinki, Finland. He has never been caught.

Content Warning: This article contains accounts of extreme physical and sexual violence against women.

The mid-1970s were marked by an unstable global landscape. As tensions simmered during the Cold War, nations held their breath, wary of the precarious balance of power that teetered on a knife’s edge. Finland, bordering the Soviet Union, knew these tensions better than most. Yet, in the late 1970s and early 1980s, the menacing spectre that silently prowled Helsinki was far more insidious and chillingly intimate.

Serial killers, with their enigmatic motives and savage proclivities, have long captivated our collective imagination, evoking a primal fear that lingers deep within our psyche. They become twisted legends, leaving behind a trail of unimaginable horrors that weave themselves into the tapestry of our history. And it was in this atmosphere of dread and fascination, the Helsinki cellar killings took root, their darkness casting a pall over an otherwise idyllic city.

Within the bounds of those streets, women walked alone with trepidation etched into every step. The shadows whispered tales of caution, their haunting voices warning of the ever-present danger that lurked in the darkness. It was when a woman’s journey home became a delicate dance between hope and fear, where the vulnerability was as palpable as the biting wind that swept through the Finnish capital.

Susanne Helene Lindholm was born on December 8, 1950, and still lived at home with her parents and siblings at an apartment in Käpylä, a neighborhood of the capital Helsinki. Located somewhat centrally, Käpylä is home to around 7500 people. It is well known for being home to the Olympic Village in 1952 and also for the canceled games of 1940. The area is also known as the first location where the Garden City Movement was attempted in the 1920s. The movement attempted to create a model housing environment when inadequate housing was a problem for workers throughout Helsinki. Ahead of its time, the movement was responsible for constructing quality prefabricated housing with plenty of green space.

By the 1970s, Käpylä was still mostly a working-class area, with some professionals also finding a home there. Susanne herself worked at Helsinki Airport, a thirteen-minute drive away. She had started her job just a few months before as a way of paying off student loans, really wanting to become a physiotherapist. At just 25 years old, she was still young and determined to enjoy herself. On August 7, 1976, she wanted a Saturday night out after a long working week. It was the summer, and Helsinki was known for its nightlife quality.

However, none of her colleagues wanted to join her on this night. Instead, Susanne met up with her sister Camilla at a hotel in Haaga, being driven there by a friend from work, Fred Koroleff, and arriving after 10pm. The two sisters then traveled to the Helsinki Club in the city center and Susanne paired off with a Norwegian businessman they met there. Susanne and the man left the club and returned to his hotel, the Hotel Hesperia. Taking her cue to leave, Camilla took the last bus back to Käpylä at 1:20am.

However, if the Norwegian man thought he was getting lucky, he was about to be disappointed. Susanne enjoyed several whiskeys at the bar with before deciding to go home. It was now 3am, and despite trying his luck one final time, Susanne refused to bring the Norwegian back home with her but did exchange numbers with him. However, as we know, the last bus had already left, meaning that Susanne would need to walk 5km back to Käpylä without money for a taxi.

Ten minutes after she left the hotel, Susanne was observed by two students walking toward the Helsinginkatu. This 2km long street runs east to west in the capital. This would be the last time that anyone saw Susanne Lindholm alive. At around 4am, inkeeping with the expected timing of her journey, she seemingly arrived back at her family apartment. While it can’t be confirmed for sure, it was then that Jouko Saarto, who lived directly below the Lindholm family, heard crying. Saarto says that he heard footsteps in the stairwell of the building, the cellar door slamming, and sounds from both a man and a woman.

To everyone else, Susanne Lindholm seemingly still wasn’t home the next morning. However, that afternoon, Sunday, August 8, a horror would be uncovered in the basement. Newly arrived tenant Esko Savolainen went into the cellar to store his bicycle, its primary function. He found the body of Susanne, alerting the caretaker, Benjamin Vihakara, and then the police. She’d been raped, strangled with a work shirt taken from her bag, and had had her head smashed into the concrete floor.

The Murder in the Cellar

Investigating the grizzly scene in the basement, Helsinki police discovered that Susanne had put up an immense struggle against her attacker, being covered in blood and having skin under her fingernails. One account says that Suzanne’s clothes were in disarray, with a child’s shovel and a ski poleon the body. Other reports say that she was covered in her coat and a jacket from work, which she usually wore about her shoulders.

In any case, it’s likely that the killer will have been covered in blood and possibly injured himself given the ferocity of Susanne’s struggle. Susanne was fit, healthy, and athletic, as evidenced by the fight she put up, which suggests that the killer was equally fit and healthy, with the strength to overcome a woman fighting for her life. Police believed that the culprit was young and potentially mentally ill, being a sexually dysfunctional loner. They also believed that the original intention of the crime was rape, with Susanne murdered when she fought back.

Police immediately began investigating the missing hour between Susanne leaving the Hotel Hesperia and returning home, wondering how she traveled. If the crying that had been heard around 4am was indeed Susanne, then that placed her at home around an hour later, a time that was about right for a brisk walk. Police hypothesized that she’d met a man on the sidewalk outside her home and conversed with him just a few feet from safety. However, just because a scream was heard at 4am, doesn’t discount the possibility that she may, in fact, have arrived home earlier. The time of death was given as between 3am and 4am, opening up the possibility she’d accepted a ride home, and the crying was heard toward the end of the attack rather than the start.

Susanne accepting a ride was the first theory the police had, with her killer traveling with her. Many considered Susanne exceptionally attractive, and police believed she would have had no problem hitchhiking if she’d wanted to. Indeed, Susanne often walked by railway tracks instead of on roads to avoid the unwanted attention of men. While this is plausible, Susanne didn’t like strangers after suffering from bullying as a child and it wasn’t long since she’d told Camilla that she would never get into a strange vehicle. Equally, it would also be a brave killer who took her home and committed the offense inside her building, not knowing who she lived with or if they were awake or waiting for her. After all, once locked in the killer’s car, he could have driven her anywhere to commit the crime.

Presuming she arrived on foot, how they targeted the victim becomes the primary question. Had this man been waiting for her and targeted her deliberately? Had the killer been acquainted with Susanne, such as a neighbor? This is certainly possible, even though he can’t have been certain when she would return. Yet, it’s also possible that such an individual could have struck opportunistically as he saw Susanne return. Was she a random victim? Or had Susanne perhaps been followed home? Again, this is possible, but the area around the Lindholm home was poorly lit and quiet, meaning there were likely dozens of better places to carry out the assault and killing. Had Susanne and her killer met at the entrance to her building? Or just feet away on the sidewalk? All questions without answers.

Despite scouring the city to find people who were at the Helsinki Club and Hotel Hesperia, as well as neighbors, taxi drivers, and anyone who may have traveled the same way as Susanne on the morning of her death, police turned up nothing, with that one hour forever remaining a mystery. During these investigations, police pulled in a nervous taxi driver, eliminating him quickly. They also extensively questioned the Norwegian man from the hotel, eliminating him just as fast with a watertight alibi. With no strong leads, the list of vague suspects and people of interest grew, the case being featured heavily in the press. As is often the case when a killing attracts the interest of the media, tips and clues came pouring in from genuine people and cranks alike, with police beginning to be swamped by the information they were gathering.

One of the many mysteries surrounding the case was how and why Susanne ended up in the cellar. The cellar was behind three locked doors, meaning that Susanne must have opened those doors. If Susanne had brought a man back home with her for sex, her parents said she wouldn’t have been timid and would have happily brought him to her room at the family apartment, eliminating the possibility that Susanne had willingly gone into the cellar for privacy. If she was a hostage at that stage, the perpetrator chose a good location to commit his crime. But how would he have known of its existence? Or that Susanne had the keys?

Hundreds of interviews were conducted by Helsinki Police, focusing on local men who had either abducted women before or were suspected of such. Fearing the killer might strike again, they even put Hotel Hesperia under surveillance. Suspect after suspect was detained for questioning, with all of them promptly released. Despite these leads, the case went unsolved. There were fresh appeals for information in 2004 when the case was reopened. Still, nothing came of it again, with not enough evidence being preserved from 1976 for modern forensic methods.

A Serial Killer At Work?

While the murder of Susanne Lindholm was initially believed to be an isolated incident, subsequent developments have led many to believe the murder to be one in a series that has been dubbed the Helsinki Cellar Murders, particularly as it was revealed that the killer had seemingly taken trophies from the body of Susanne — two gold rings and a purse.

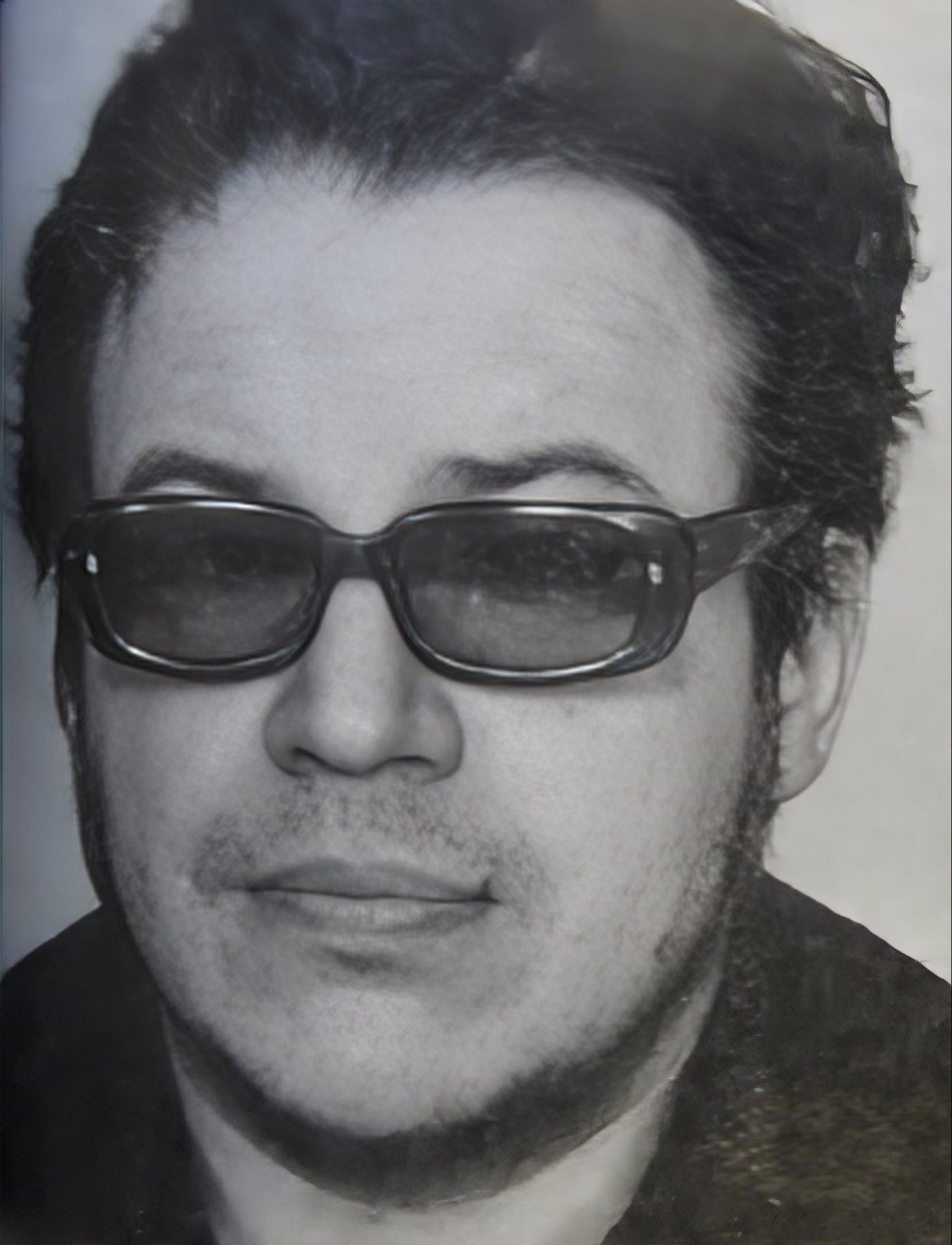

It was in March of 1979 that 28-year-old travel agent Helena Korlin vanished from the Etu-Töölö area of the capital, with some reports in the press claiming she had been a friend of Susanne Lindholm. She lived with her mother and had a young son. Helena was reported missing by her sister on April 2 and was last seen leaving a bar in the company of convicted rapist Carl-Erik Björkqvist, known as “the goat of Punavuori” because of how many casual sexual relationships he had. Police quickly questioned him over Helena’s disappearance. He admitted leaving the bar with her and returning to his apartment, denying seeing her afterward. Police claimed to have searched his apartment and found no trace of Helena. However, later accounts from private investigators suggest this wasn’t true.

Björkqvist was from a highly influential family, and these later accusations suggest that police were lax in investigating him. In truth, Björkqvist’s bathroom and elevator were covered in blood, and it was only when more blood was also found in a car he had recently sold that the police acted. In May, police arrested Björkqvist, and he confessed, Helena’s dismembered body being found at a landfill site. She had been stabbed and strangled, with Björkqvist dumping her body in a dumpster like trash.

Under questioning, Björkqvist admitted that he’d killed Helena after she rejected his advances, and police began to question whether she was his first victim, seeing similarities to their theories in the Lindholm case. Ultimately, they abandoned the idea after not finding evidence to link Björkqvist to the events 1976. He had form, however, and had raped a 17-year-old back in 1971, with another brutal attempted rape on his record from 1974. Both crimes were said to have shown significant violence.

Thanks to his influential family and undoubtedly good lawyers, Björkqvist served just 10 years for the rape, murder, and dismemberment of Helena Korlin, being released in 1990. During his time in prison, the killer was the focus of significant female attention. He received 300 marriage proposals, including from a rich British widow, the former wife of a professor. Björkqvist married the woman and lived comfortably out of a North London hotel.

A lack of justice envelops the entire case and sadly doesn’t end with Susanne Lindholm. While Björkqvist may not have been her killer, somebody was, and it seems they struck repeatedly.

On December 6, 1980, over four years after the murder of Susanne, 41-year-old mail carrier and mother-of-two Seija Tuulikki Kekkonen was raped and murdered in the basement of her own apartment building in the Kontula area of the city. It was Independence Day in Finland, and there would likely have been celebrations all over Helsinki the night before and into the early hours of Independence Day morning. Seemingly some had taken the opportunity to combine the celebrations with Christmas festivities, as Seija had been at such a party the night before, the event taking place at a restaurant.

A resident at her building found the body later that morning, with police revealing that a rape attempt had been made. Again, just like with Susanne, thousands of people were questioned in the case, although this time, tips weren’t as forthcoming, and the police made little progress. Nobody saw anything at the apartment.

Around two months later, on January 30, 1981, 42-year-old Helka Onerva Ketola would be killed. Helka was a former bookbinder who had retired thanks to a back injury. The area she lived in was known to be rough, with the police having to be called on a number of occasions. On this night, she’d spent the evening at a bar in Kallio before visiting a friend’s house.

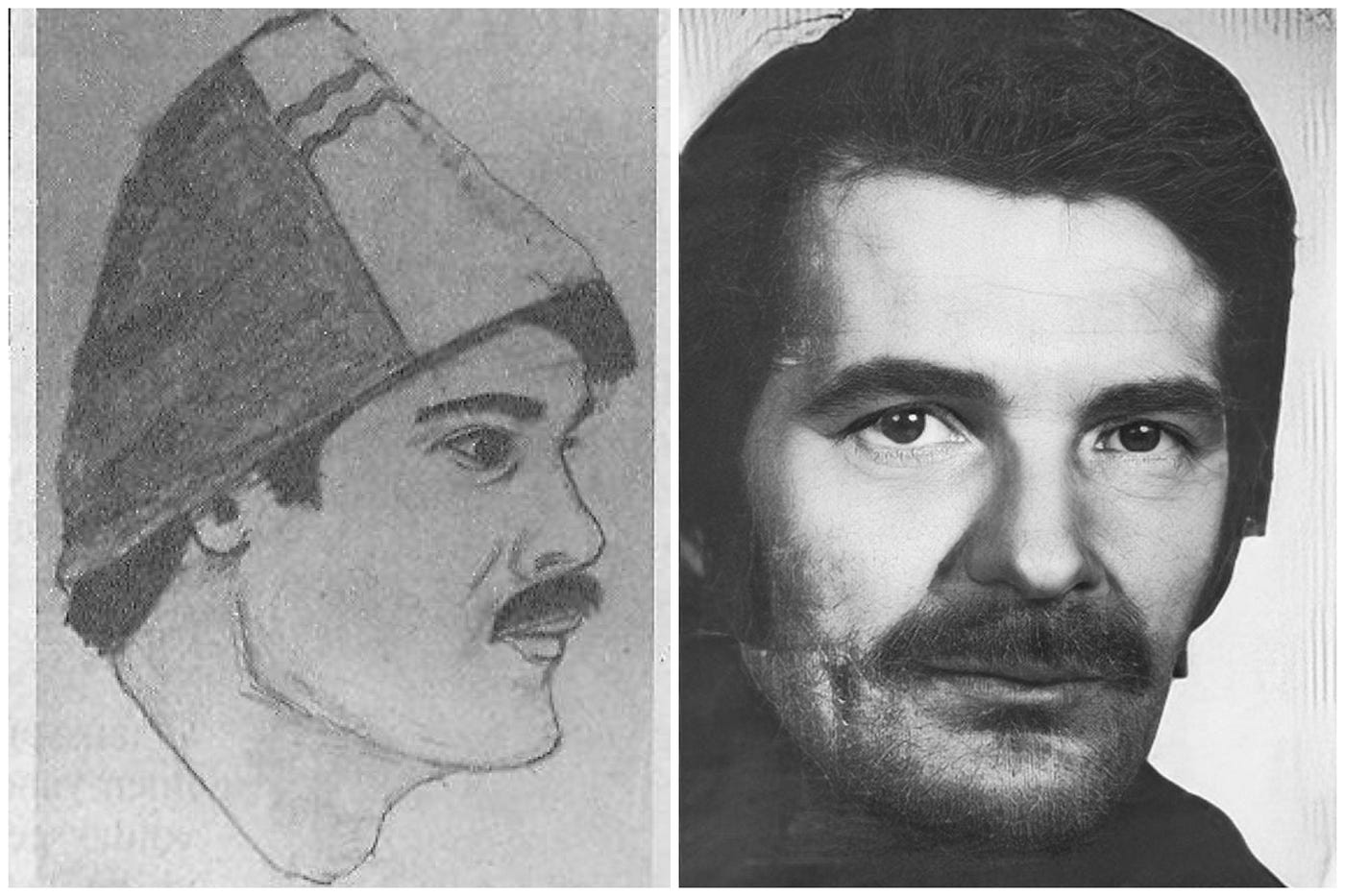

This time, witnesses saw the victim with a man who was believed to be her murderer. They described him as between 25 and 30 years old, and there was an argument before the two entered the cellar. Violent clashes were heard, and the killer made off with her bag containing her keys and bank book. At the scene, a beanie hat was discovered, and witnesses confirmed that it belonged to the man seen with Ketola before her murder.

The similarities between the cases are obvious and startling. In all three cases, the victim was taken to the basement of their own building, and either raped or rape was attempted. The killer struck against a victim who was returning from a night out on all three occasions, with January 30, 1981, being a Friday and January 30, 1981, being a Saturday. Like Lindholm, Helka Ketola was strangled, with Kekkonen’s cause of death never officially revealed.

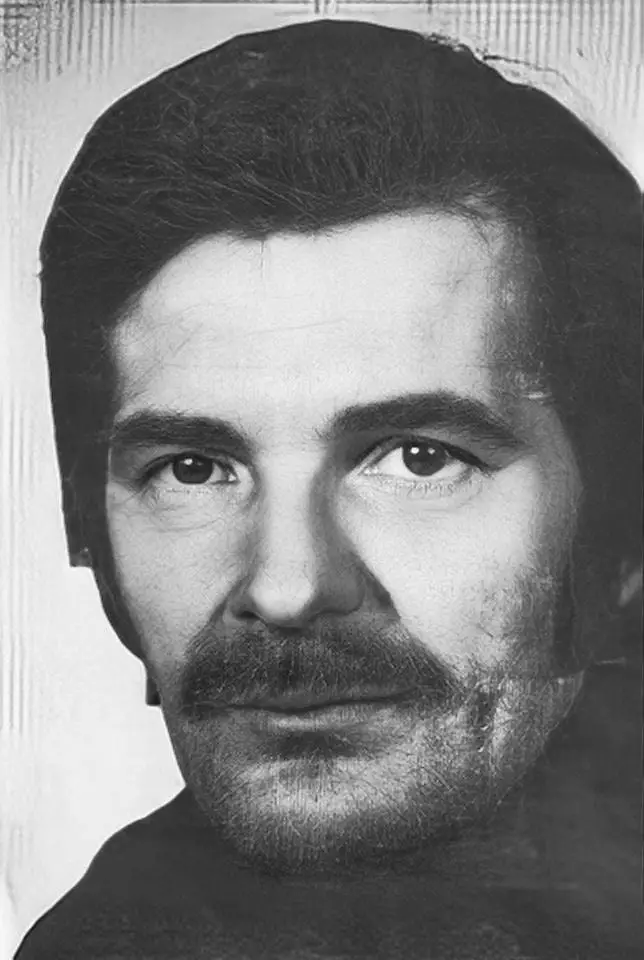

On July 6, 1981, the Helsinki Cellar killer may have murdered his final victim, even though a basement didn’t feature in the case. On this day, Jalo Eetu Seppänen, a bus driver from the nearby city of Espoo, raped and murdered Helena Mäntylä.

The shy and timid Helena was on a night out with friends in the centre of Helsinki and was on her way back home, having taken the 11pm bus. Tragically she could have taken the number 45 but as it was full of rowdy teenagers, she decided to take the number 32 even though it would be an additional ten minute walk home. She left the bus at 11:38pm and needed to walk through a forst and tunnel. When she arrived, Seppänen was waiting. He punched her in the face, dragged her into the bushes, raped her, and then strangled her to death. She was just 18.

Seppänen was caught when he raped a 13-year-old schoolgirl on the morning of January 15, 1982, and in his arrogance suggested the two meet for sex that same afternoon. The police were waiting when he actually turned up. Already a convicted sex offender at the time of his arrest, he had used strangulation during previous sex attacks where the victim survived and took trophies. In 1980, he had raped a hitchhiker and absurdly received a suspended sentence, depsite a previous allegation of rape againts him.

Born in 1948 and one of eleven children, Seppänen had worked in forestry and construction before becomming a bus driver. His job gave him easy access to potential victims. He would have been in his 20s when 30s during the killings and although short was in athletic shape, having been a boxer in his youth. He also matched the police drawing in the Helka Ketola case.

Under questioning, Seppänen admitted killing Helena Mäntylä and revealed his deep hatred of women. He was intent on avenging himself against them, with his malice seemingly derived from the end of his marriage. That marriage ended just before the murder of Susanne Lindholm, and Seppänen had descended into drink and drugs soon after. However, his reasoning may be as much an attempt to pass moral responsibility than any genuine psychological insight.

As police didn’t have the evidence to charge Seppänen with anything else, he was released in the 1990s and immediately committed another rape. After serving more time in prison, he’s believed to still be alive and currently a free man.

Whether the Helsinki cellar victims are the work of one individual is a matter of some debate, with the police and public alike divided. Many believe that Jalo Seppänen is also guilty of the murders of Susanne Lindholm, Seija Kekkonen, and Helka Ketola, alongside the one confirmed victim, Helena Mäntylä. Others contend that while the crimes seem alike, there are significant differences. For example, the murderer of Helka Ketola made off with her bag, and, were it not for the surrounding context, many would likely believe it a robbery. Equally, Seija Kekkonen was said to live in fear of her husband. She initially didn’t want to go to the Christmas party as she feared a jealous reaction. In that case, the “basement” was at ground level, meaning there are significant questions about why no sounds were heard.

Conclusion

The Helsinki cellar killings remain a haunting and unresolved chapter in the city’s history. The brutal killings of Susanne Lindholm, Seija Tuulikki Kekkonen, Helka Onerva Ketola, and Helena Mäntylä left a trail of fear and unanswered questions. While there were similarities among the cases, such as the victims being targeted after a night out and the gruesome manner of their deaths, no definitive evidence has linked them to a single perpetrator.

The investigation into these crimes was fraught with challenges and frustrations. Despite extensive police efforts, including countless interviews and appeals for information, no breakthroughs were made. The case attracted attention from the press and generated numerous tips, but the sheer volume of information often overwhelmed investigators.

Decades have passed since these unspeakable crimes took place, and the chances of solving them grow slimmer with each passing year, with the wounds inflicted upon Helsinki remaining open. The victims and their families were denied both closure and justice, with the Helsinki Cellar Murders representing a failure of the criminal justice system to bring the perpetrators to account.

The Helsinki Cellar Murders continue to serve as a reminder of the horrors that can lurk beneath the surface of even the most idyllic cities. The search for justice and closure for the victims and their families endure as the memory of these victims lives on in the collective consciousness.

As Helsinki moves forward, it does so with a renewed commitment to safety, justice, and remembrance. The city stands united, determined to prevent such atrocities from occurring again. The Helsinki Cellar Murders will forever serve as a haunting reminder of the darkness that can reside within humanity, urging us to remain vigilant and compassionate, ensuring that the victims are never forgotten.