The Bennington Triangle: Serial Killer or Coincidence?

There are some areas of the world that legend has made mysterious. One such area is the so-called “Bennington Triangle,” an area of land around southwestern Vermont but spilling over into other states around the Green Mountain National Forest. Author Joseph A. Vitro has popularised the triangle’s existence and its link to folklore and a large number of disappearances in the vicinity over a short period.

The first noted disappearance in the Bennington area was Middie Rivers, aged 74. On November 12, 1945, Rivers was guiding a group of four hunters while out in the mountains around the area of Hell Hollow, southwest of Glastonbury, when he got ahead of the group and vanished. Rivers was an experienced hunter and fisherman and familiar with the local area, leading rescuers to hope that he would be found safe and well. An extensive search was undertaken for Rivers, but the only trace ever recovered was a rifle cartridge in a stream, with investigators speculating that it had fallen from his pocket.

Taken on its own, Rivers vanishing would not be particularly unusual. While he was experienced in the area and wild, he was 74 years old, and the incident could be written off as an accident. However, just over a year later, the next disappearance took place.

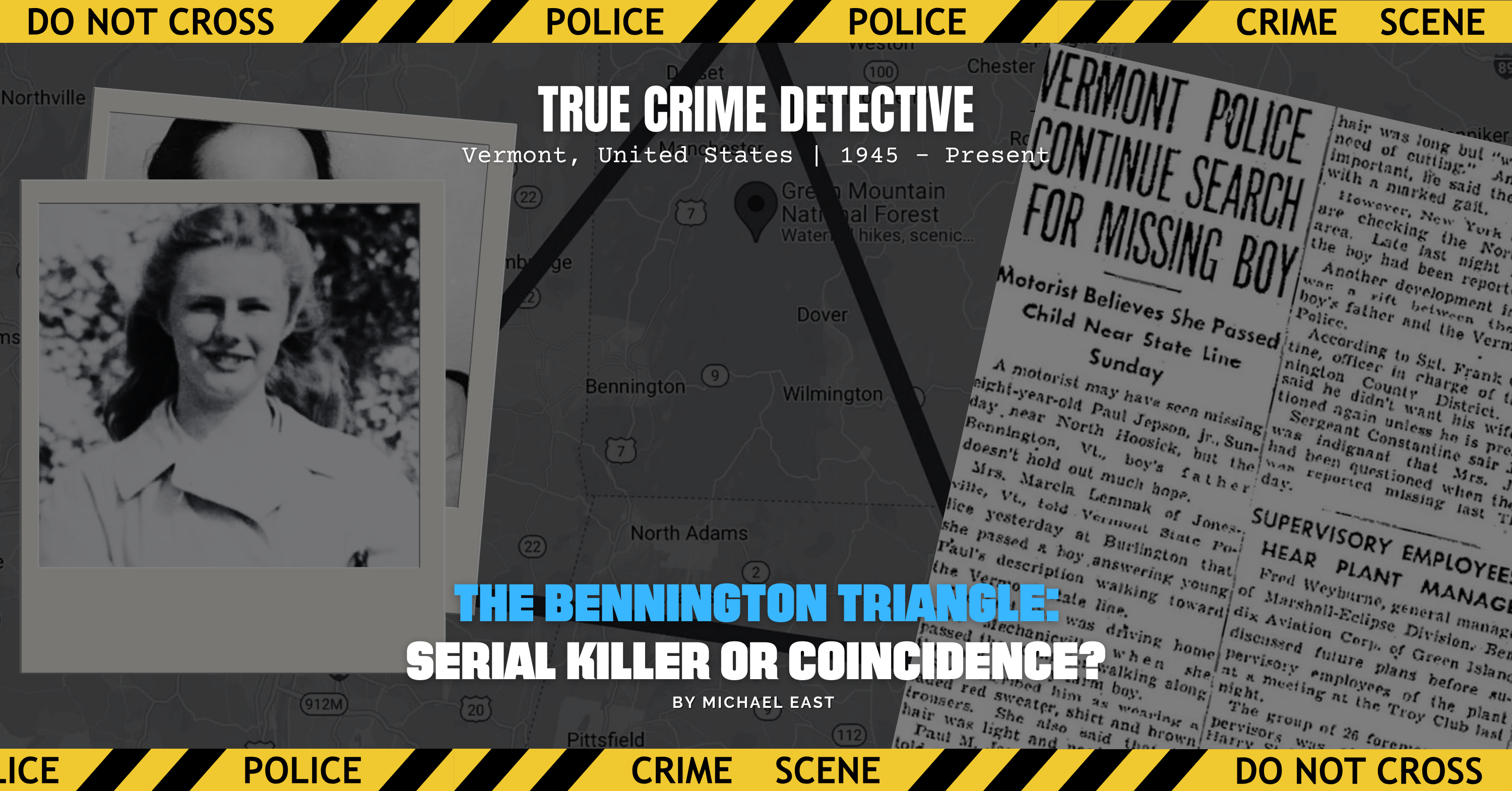

On December 1, 1946, Paula Jean Welden, 18, went hiking on the Long Trail road, the same area that Rivers had vanished from. She was the eldest of four daughters, with her father being the noted industrial engineer and architect William Archibald Welden. By 1946, Paula was a sophomore at Bennington College and a popular student. Despite this, she could not persuade anyone to come with her on the trek, it being the first time she’d experienced the Long Trail.

Perhaps her inexperience led her to start the hike without anything in the way of safety provisions. She took clothes only suitable for that afternoon, had no bag, no money, and likely nothing in the form of emergency supplies or kit. While this may sound irresponsible, it should be said that she never expected to be outdoors longer than a single afternoon. She hitched rides to the area and once there went in a northerly direction, talking to other hikers along the route, last being seen around the Fay Fuller Camp and possibly heading into the woods as darkness began to set in.

When Welden didn’t return that evening, her roommate thought little of it, thinking that she had probably gone to the library for some additional study. However, by the following day, it became apparent that this wasn’t the case. The college was informed, followed by the State’s Attorney and local sheriff’s department, with nobody finding any trace on her on campus. Despite investigations, it wouldn’t be until a few days later that anyone realized she’d gone to the Long Trail, one of the hikers she’d talked to raising the alarm after seeing Welden’s picture in the newspaper.

Emergency teams and locals searched the area for weeks, including students from Bennington College, the institution being shut for several days to allow them to join the hunt. Family members, volunteers, firefights, and the National Guard all joined in, with the ground search being complemented by aircraft. Like with Rivers, not a trace was found.

The lack of evidence to point to Welden even being there led to many theories being developed about what had happened to the young student. Some speculated that she’d actually run off to start a new life or secretly eloped with an unknown boyfriend. Those thinking more pessimistically suggested she may have committed suicide or been kidnapped. However, the darkest suggestion was that Welden had been murdered, with a possible suspect even being linked.

Fred Gadette was a local lumberjack who lived along Harbour Road, part of the trail that Welden had walked. He was in the middle of an argument with his girlfriend when the young woman walked by, with Gadette leaving in a jealous rage not long after. His statements about what he did after leaving his girlfriend were contradictory, sometimes saying he’d headed home to his shack and on other occasions stating that he’d driven his truck up the trail in the same direction as Welden.

Gazette’s lies to the police made him a person of interest in the case during the active investigation and once again when the case got reopened a few years later in 1952. Reports from acquaintances suggested that he had said that he knew where Welden was buried on at least two occasions, telling investigators that it had simply been idle talk. Despite the indications, there was no evidence that a murder, or any other crime, had been committed and nothing definitive to link Gazette to Walden’s disappearance.

The police investigation into the case was heavily criticized by many, including Walden’s influential father, with all pointing out that the lack of a statewide police force at the time hampered the investigation. Within seven months of Walden going missing, the Vermont legislature had created the Vermont State Police. It would be easy to dismiss any link with just two cases, both with differing features. But Rivers and Walden wouldn’t be the end of the disappearances in the so-called “Bennington Triangle,” far from it.

James E. Tedford would be next. Tedford was a veteran and a resident of the Bennington Soldiers’ Home who, on December 1, 1949, had been visiting relatives in St. Albans. They accompanied him to a local bus, and he was never seen again. It was precisely three years to the day since Paula Welden had gone mysteriously missing.

What makes the Tedford case even more puzzling is that he appears to have vanished from the bus itself. Witnesses all agree that he got on board the vehicle and was still on the bus at the last stop before he would have arrived in Bennington. However, somewhere between those two stops, he seemingly vanished into thin air. His baggage was still in the luggage rack, and there was an open bus timetable on his now vacant seat.

Obviously, Tedford didn’t vanish into thin air, no matter how much paranormal aficionados wish to believe it. However, what really happened that day remains a mystery.

The subsequent disappearance is perhaps the saddest of all, being eight-year-old Paul Jepson on October 12, 1950. Jepson had accompanied his mother in her truck, and she left him alone to feed some pigs. Jepson was likely excited, with children often eager to see and participate in their parents’ work. However, Jepson’s mother left the boy alone for up to an hour, and when she returned, he was gone.

The young boy was wearing a bright red coat, with desperate search teams hoping that it might make him more visible, yet nothing was ever found. One story states that tracker dogs managed to get the boy’s scent and tracked him to a nearby highway. Local legend says that Paula Welden had last disappeared alongside the same stretch of road, yet as with most such urban legends, it must be taken with a healthy dose of salt.

The last of the canonical five victims of the “Bennington Triangle” is Frieda Langer, who vanished just sixteen days after Jepson on October 28, 1950. Langer, 53, had been camping with family near the Somerset Reservoir and decided to hike alongside her cousin, Herbert Elsner. During the walk, Langer fell into a stream and needed a change of clothes, asking Ellsner to wait where he was, and she’d return shortly. However, she never did.

A confused Elsner headed back to camp and was alarmed to find his cousin hadn’t returned and that nobody had seen her. Once again, major searches were undertaken involving hundreds of searchers, aircraft, and helicopters, but no trace of the missing woman was found. However, unlike with the other four cases, the eventual outcome would be different this time.

On May 12, 1951, over half a year after Langer disappeared, a skeletonized body was found three and a half miles from the family camp, with the area having only been lightly searched at the time of Langer’s vanishing. The remains were indeed those of Frieda Langer, and given their condition, no cause of death could be determined. Still, The North Adams Transcript would state that officials had concluded she “fell down [a] bank and drowned in [a] hole on the dark and rainy night of her disappearance.”

All of these incidents may have entirely rational explanations on the face of things. An old man gets lost in the mountains, an inexperienced hiker gets lost or meets a man wishing to do her harm. A young child wanders away and suffers an accident; a woman loses her way in the woods. Yet, the short time between them is concerning, as is the fact that they all took place in the same general location. Equally, while authors and commentators only usually list Rivers, Welden, Tedford, Jepson, and Langer, the alarming thing is that the disappearances kept happening after 1950 and may have begun even earlier.

Author Michael C. Dooling links two other disappearances with that of Paula Welden in his 2011 book Clueless in New England: The Unsolved Disappearances of Paula Welden, Connie Smith, and Katherine Hull. The two cases he links are the 1936 vanishing of Katherine Hull and the 1952 disappearance of ten-year-old Connie Smith.

Hull was 22 when she vanished from Lebanon Springs, New York, while visiting her grandmother. A deer hunter would discover her remains in the crotch of a tree seven years later in December 1943, with investigators only finding the skull and hip bone. The remains were located four miles from her grandmother’s house, with police concluding that she had simply walked off while her parents were unloading luggage from their vehicle.

On July 16, 1952, Connie Smith was yet another to go missing, vanishing from Camp Sloane in Lakeville over the border in Connecticut. Smith was a typical happy ten-year-old and loved animals and traveling to new places. Part of her vacation was spent at Camp Slone, and she’d been enjoying her time there, begging to be allowed to stay longer when her mother came to visit on July 14. Her mother turned her request down, however, and Connie would be going home on July 23.

Before she could, however, things seemingly turned sour for her at camp. There was a fight with a group of girls, and she was punched in the face, suffering a nose bleed. She told those she shared a tent with she’d be skipping breakfast and walked out of the camp, heading down Indian Mountain Road. Witnesses describe her picking flowers and innocently asking passers-by for directions to Lakeville. She was last seen on Route 44 attempting to hitchhike.

While some speculate that the young girl may have had an accident and succumbed to the elements, this seems to be a way of avoiding the fact that she likely got picked up by a vehicle and was murdered. There is a suspect in the case, William Henry Redmond. Redmond was a former truck driver and carnival worker from Nebraska, having been charged in 1951 with the murder of an eight-year-old in Pennsylvania.

The case against Redmond fell apart when a police officer refused to disclose a confidential source, and many believe that not only was he guilty, but he would go on to kill again and again. He is a suspect in the 1951 disappearance of Beverly Potts, 10, in Ohio and the disappearance of seven-year-old Maria Ridulph in Illinois.

While genuine monsters such as Redmond are likely responsible for some of the disappearances in the Bennington area, it would be remiss not to mention the popular paranormal theories that abound in the case, with the claims, of course, being popular with more sensationalist tellings of the tale. Like with the Bermuda Triangle, aliens, of course, get a mention, as does Bigfoot, or a local variation named simply the Bennington Monster.

With “sightings” having taken place since the 1800s, the alleged monster has been claimed as responsible for attacking a stagecoach with such ferocity that it was able to tip the vehicle, with petrified witnesses saying it was hairy, black, and over six feet tall. Legend tells of how in 1943, the body of hunter Carol Herrick was found 10 miles northeast of Glastenbury surrounded by giant footprints, with the medical examiner concluding he’d been squeezed to death.