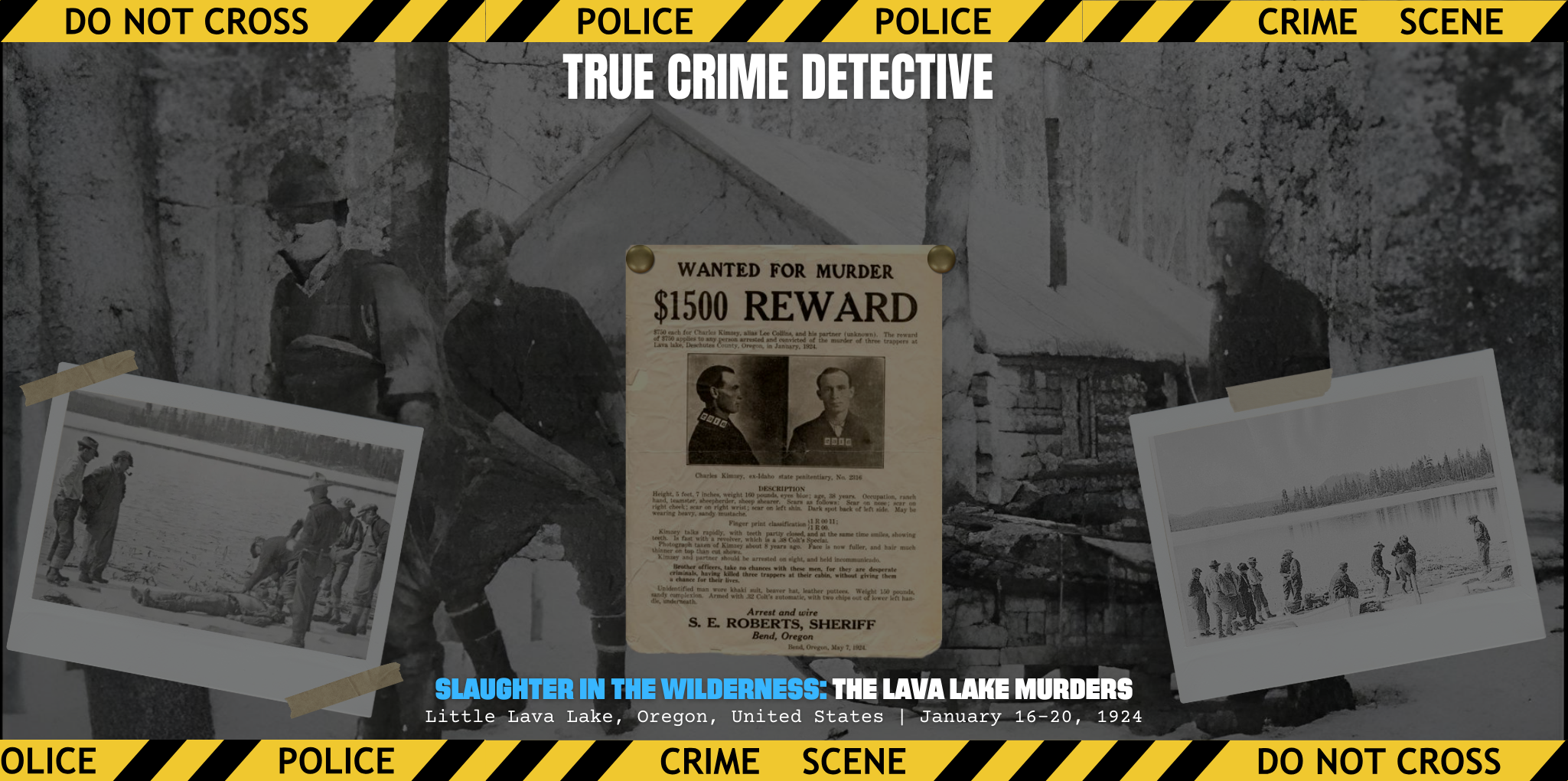

Slaughter in the Wilderness: The Lava Lake Murders

Few genuinely appreciate how harsh the American wilderness can be. In 2025, we have the benefit of GPS, cellphones, and all manner of survival aids that make tragedy rare. However, as late as only a few decades ago, the wild was indeed a place to be both respected and feared. While nature is so often the blameless culprit of these tragedies, all too often, it is humanity itself that is the instigator, the wilderness perhaps bringing out the most primal and bestial urges in men. While these urges can be understood in times of need and survival, it should be remembered that the most rudimentary of these urges is often not hunger or the need for warmth; it is greed, followed swiftly by vengeance. In 1924, these most base of desires would have tragic consequences for three men, brutally slain in the snow-covered Oregon mountains all for want of money and an act of revenge that was served both cold and bloody.

Edward Nickols, 50, Roy Wilson 35, and Dewey Morris, 24, sensed an opportunity. Wilson and Morris worked as loggers for the Brooks-Scanlon Company and were experienced outdoorsmen. In the winters, their friend Nickols would become the caretaker of a lakeside cabin at Little Lava Lake, Oregon. The three decided to work the winter that spanned 1923 and into 1924 as fur trappers, basing themselves at the location and anticipating a quality haul. However, Nickols had a second motive for asking Wilson and Morris to stay, being worried for his safety after being threatened earlier that year by a former partner.

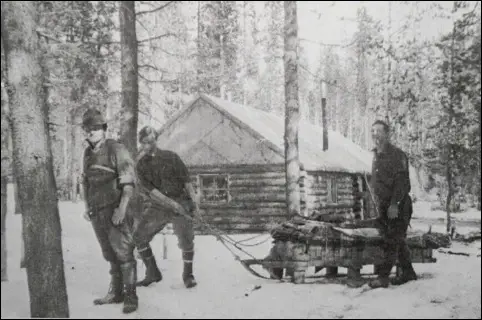

Situated in the wilderness, the place was located high in the Cascades and was remote, yet it also held significant opportunity for trapping. The cabin itself was owned by a local logging contractor named Edward Logan, and all three were in high spirits as Christmas approached, their work going exceptionally well. While the men would be missing the festive season, the money they would be bringing home undoubtedly more than made up for it. Nichols, the head of the party, at least got to spend a small amount of time back in the nearest city, Bend, returning home with a pack of quality furs before headed back to the cabin.

Nickols, Wilson, and Morris’ good fortune continued, and on January 15, 1924, they were visited by Allen Wilcoxen, a resort owner who was tracking his way from Fall River to Elk Lake. The man stopped at the cabin during his journey and reported all present were in high spirits, and no problems were to be found at the remote location. However, following his departure, none of the men would ever be seen alive again, news from the cabin falling eerily silent.

The silence from the cabin soon started to raise suspicion in Bend. All three trappers came from the city, and Dewey Morris’ brother became quickly alarmed when he noticed that mink traps set in the vicinity of the cabin had not been emptied. He was joined in his concern by Superintendent Pearl Lynnes of the Tumalo Fish Hatchery, and a search party was organized to instigate on April 13. The party was joined by H.D. Innis. Upon arrival, the new trio discovered the Lava Lake cabin wholly abandoned with the men’s clothes, guns, and equipment still lying where they had been abruptly left. The dining table had been set for breakfast, and there was burnt food on the stove. There was no sign of any of the occupants except for a cat that had found itself trapped inside. Emaciated, the feline was still alive, having undoubtedly managed to forage some of the food. The men believed it may have been there for some months.

Perplexed, the search party looked outside and found the men’s sled was missing alongside five valuable foxes owned by Edward Logan. Further investigation found a blood-covered hammer inside the now empty pen.

“Out in back of the trappers’ cabin one hundred feet was a fox pen, enclosing five very valuable foxes owned by Ed Logan. The trappers, in return for the use of the cabin during the winter, were feeding the foxes and looking after them.”

Deschutes County Sheriff Claude L. McCauley

Moving out to check the traplines, all manner of animals were discovered dead and frozen, including marten, foxes, and a skunk. Clearly, something alarming had happened at the cabin, the men quickly returning to Bend. Both Logan and Deputy Sheriff Clarence A. Adams were summoned, and the expanded party arrived the next morning.

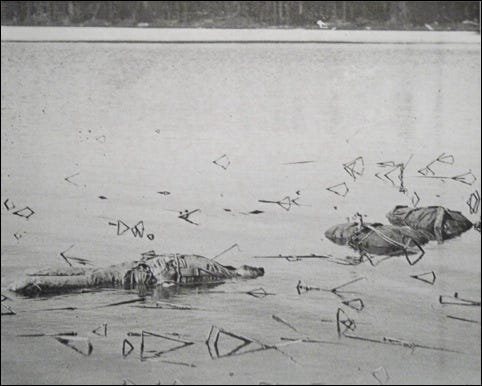

With the added assistance, the missing sled was soon discovered close to the shoreline at Big Lava Lake with clear bloodstains. The alarm would only be raised further when similar bloodstains were found on a trail leading into the lake itself with clumps of hair leading to the worst possible suspicions. Investigating the water, a depression in the ice not far from the sled suggested a more recent hole had frozen over. Now being April, the lake had thawed enough that the ice could be broken and a boat utilized in a search, and the search party soon discovered the bodies of all three missing men. Nickols, Wilson, and Morris had been murdered.

“Hastily trying ropes to the corpses, the grim procession headed for shore. Here the bodies were fastened to the shelf ice for the night. Adams donned his snowshoes and made for town on the run.”

Deschutes County Sheriff Claude L. McCauley

Deputy Sheriff Adams left immediately for Bend to raise the alarm and further investigations soon found more blood and hair alongside a human tooth. Underneath a tree near the cabin were found four of the missing foxes, all expertly skinned with their fur missing. After the scene was thoroughly searched, the three bodies were taken back to the city for autopsies. The bodies had all been fully clothed but showed significant mutilation from gunfire, with all three seemingly initially raked across the torso with shotgun blasts before Nichols and Wilson were executed point blank with a handgun. Morris had been beaten to death with the hammer discovered in the pen.

Investigators soon came to the theory that the men had been lured from the cabin during preparation for breakfast and quickly ambushed. Nichol’s watch had stopped at 9:10. The initial attack had been ferocious, with Wilson’s right shoulder obliterated by the shotgun and Nichols hit in the face, his jaw shattered. Wounded, the two defenseless trappers were then executed. Morris was killed separately from the rest, having possibly tried to escape the carnage. Also injured, he was soon run down and beaten to death with the hammer. The coroner concluded that the trio had been killed in late December of 1923 or early 1924, tying with the last sighting being January 15.

Police suspected that more than one individual had been involved in the slaying. Not only was the utilization of different weapons telling, but Wilson had also been a former U.S. Marine. It seemed unlikely that a single person could have successfully overcome three strong men, one a marine, even despite being clearly well-armed.

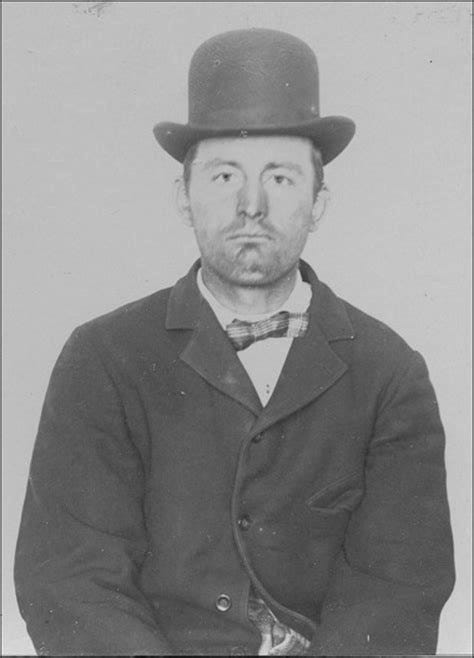

Police soon began to consider suspects and realized that the killings had to have been carried out by somebody familiar with the area. Without expertise in the wilderness, the cabin was almost impossible to find in the snow. After considering a local woodsman by the name of Indian Erickson, police quickly dismissed him after an alibi was presented and turned their attentions to one Lee Collins. Collins’ name had been raised by Edward Logan not long after the discovery of the bodies given a known quarrel, being the former partner that Nichols had been worried about. The previous summer, he had been employed at the lake and had been charged with theft after stealing a wallet from his own partner. During the affair, Collins had promised to return and kill Nichols. The police came to suspect that he’d held a grudge over the case. Upon further investigation into Collins’ background, police would soon discover that he wasn’t “Lee Collins” at all.

Collins was, in fact, Charles Kimzey, a fugitive from justice with a far more severe record than the mere stealing of a wallet. Kimzey had stood accused of involvement in a 1923 stagecoach robbery that had seen W. O. Harrison, the driver, thrown down a well. Kimzey had hired Harrison to drive him to Idaho but on the way had feigned a call of nature and overpowered his driver, binding both his hands and feet with bailing wire. This would have been enough to make off with the stagecoach, but instead, Kimzey gave the driver a dose of poison and threw him down the abandoned well, seeking to kill the witness and leave the body where nobody could possibly find it. Harrison had amazingly survived, vomiting up much of the poison and managing to loosen his bonds. He crawled out of the well and found aid at the nearby Last Chance Ranch. Kimzey was arrested on charges of robbery and attempted murder, but before he could be brought to trial in Bend, he had fled.

With a clear suspect in mind, police began to question potential witnesses, and news of the crime soon spread. Vitally, one witness, a traffic officer by the name of W.C. Bender, reported that Kimzey had approached him in Portland on January 24. The officer stated that Kimzey had asked for directions to a local fur dealer and was carrying a burlap sack, likely containing pelts. Directing police to the Schumacher Fur Company, it became clear that Kimzey had sold “his” wares for $110. He had shown Schumacher the license of Ed Nichols, and the furrier also reported that he had been in the company of a second man. While the one believed to be Kimzey was described as quiet, the second mystery man was talkative and friendly, trying to charm Schumacher.

A reward of $1500 for Kimzey’s arrest in connection with the triple homicide was soon posted, and an extensive hunt was undertaken all over the Northwest, but it was too late; Kimzey had got away. An experienced woodsman, it seems possible that he may have laid low for years using his skills in the wild or simply disappeared into a nearby state. The case was cold and soon shelved, only becoming active again when Claude L. McCauley became Deschutes County sheriff several years after the killings. McCauley made it a personal mission to hunt down Kimzey, traveling over 10,000 miles in just four years as he followed up leads in every state surrounding Oregon. In February of 1933, nine years after the murders, there would be an apparent breakthrough.

On February 18, 1933, police in Kalispell, Montana, arrested a hermit going by the name of “Bob Bales,” reporting that the detainee bore a striking resemblance to the fugitive Charles Kimzey. However, investigators concluded that prints and pictures of the man didn’t tally with Kimzey and let the man go. It would be an interesting footnote in the case as just weeks later, on March 10, the actual Charles Kimzey was spotted right there in Kalispell. Arrested, he soon admitted his identity and stated he knew nothing of Bob Bales, having seemingly lived in Colombia Falls. He denied all knowledge of the Lava Lake murders.

“I haven’t heard the name ‘Kimzey’ for years… They think I killed those trappers in Oregon, but I didn’t. I was in Colorado working on the Moffat Tunnel at that time.”

Charles Kimzey

Interestingly, Kimzey himself brought up the subject with investigators who had made sure not to mention the case beforehand. Despite this implicating fact, Kimzey claimed an alibi. According to his account, he had spent the entire period over Christmas at the Moffat Tunnel, even eating his Christmas dinner inside of it. His alibi seemingly checked out yet apparently wasn’t thoroughly investigated. Police feared privately that there was no evidence against him in any case. Despite this, two officers brought the suspect back to Bend on March 16, 1933, and he was bound over, being placed in the Deschutes County jail. Still hopeful of indicting him for the murders, Sheriff McCauley began to gather the evidence. However, he was to be quickly disappointed as neither Bender nor Schumacher could make a positive identification of Kimzey as the man they had seen in Portland in 1924.

“Schumacher…stated that he would hesitate to identify the man positively after a lapse of nine years, especially when Kimzey’s life might depend on his testimony. He thought he might be the same man, but inasmuch as Kimzey had aged considerably since he last saw him and had grown quite bald, he did not care to swear he was the right man”

Deschutes County Sheriff Claude L. McCauley

Realizing Kimzey was in danger of walking, the police began to look at the other crimes for which the suspect was accused. He was wanted for murder in Utah over another stagecoach robbery; in Idaho, he had escaped from a 15-year sentence for burglary. Equally, he was still wanted for the attempted murder and theft in Bend. McCauley sent for W. O. Harrison, the stagecoach driver who had been thrown down the well in 1923. He was now living in California and had no problem identifying the man who attacked him all those years ago. McCauley knew he finally had his man and had enough to put him away, all be it not for the Lava Lake killings.

Kimzey pled his innocence, but Harrison’s testimony sealed his fate, and he was found guilty after just three hours of deliberations by the jury. He was sentenced to life imprisonment at the Oregon State Penitentiary, an unusually harsh sentence that many believed had taken the Lava Lake massacre into account. Kimzey was released in 1957 and spent the rest of his life in Idaho.

While the triple homicide is officially unsolved, almost everyone involved with the case believed that Charles Kimzey was responsible. While there was no direct evidence to link him to the killing, he had a clear tendency to extreme violence and had already threatened to kill Nichols. His mysterious appearance in Portland with fur seemingly connects directly to the skinned foxes found at the cabin. However, this account from the Schumacher Fur Company also seemingly confirmed what police had suspected — that a second man had been involved in the affair.

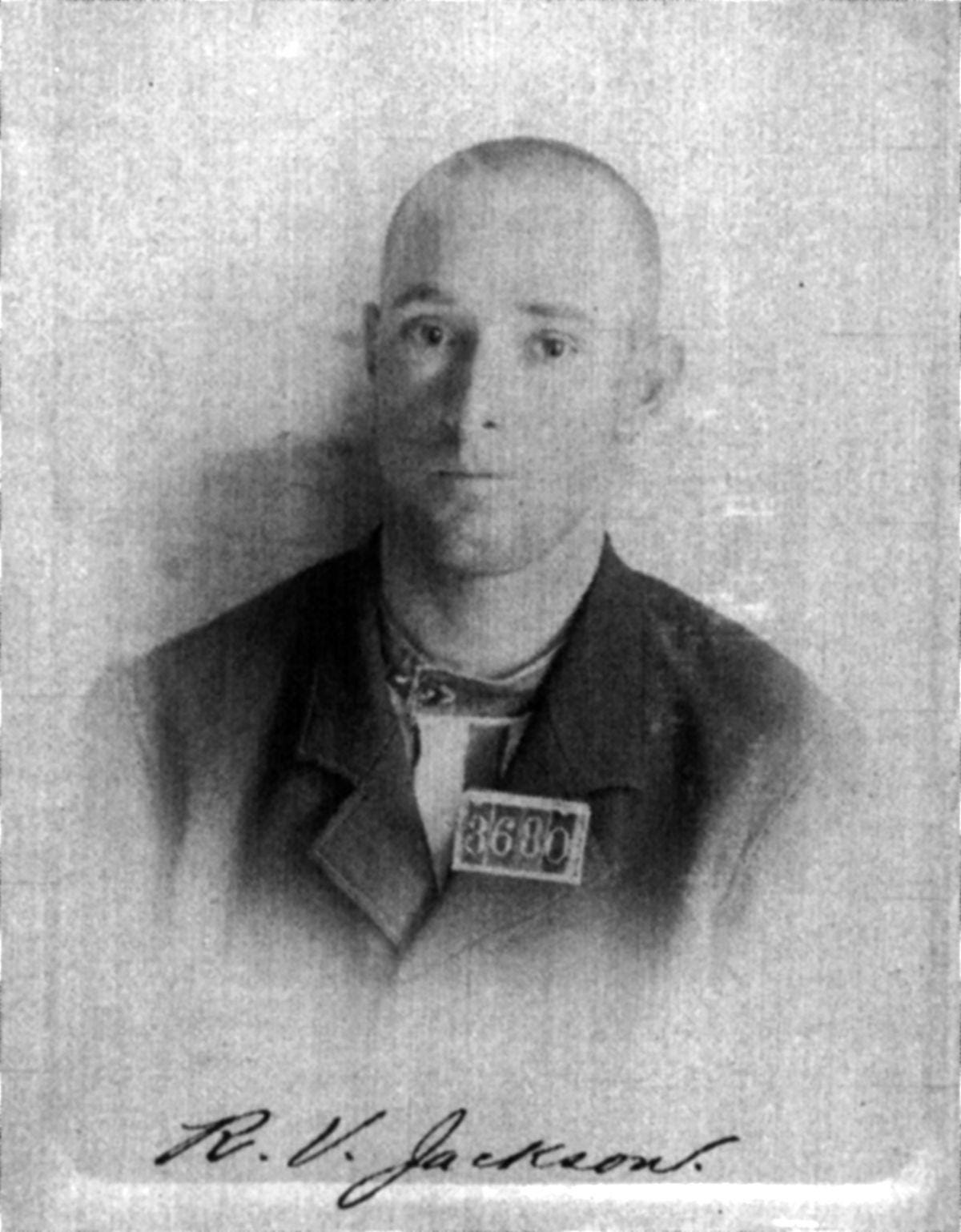

In 2013, Melany Tupper proposed Ray Jackson Van Buren as the man who had accompanied Kimzey in her book The Trapper Murders. Hailing from Sweet Home in Oregon, Van Buren was known as the “angel of death” who had been linked to possibly a dozen unsolved murders throughout the state. Known as a good talker, Van Buren was considered psychotic, and Tupper showed extensive links between the men. The author has extensively followed Van Buren’s trail, pointing the finger in the same place for another book, The Sandy Knoll Murder.

Van Buren was an educated man, having attended college and achieved a teaching certificate. However, in 1895 he was the victim of tragedy himself, witnessing his uncle’s wagon being hit by a railroad train. Tupper recants that Van Buren saw the train mangle the horses and run directly over his relative’s head. This incident seems to have been the spark for a downward spiral in his life, soon being arrested for forgery. Sent to the state penitentiary for two years, a life of crime began.

Amazingly to our modern eyes, despite his crime, he still found work as a teacher. He was noted for bringing a baseball bat and revolver to class, dealing out corporal punishment with relish. He often found himself on the fringes of mysterious murders, frequently for monetary gain and usually via a combination of beating and firearms. In a dozen murders, he was always there to offer a friendly helping hand to investigators, his charm seemingly washing away any suspicion he may have been involved in the death of many acquaintances. He committed suicide in 1938, shooting himself in the chest with his own rifle. He was never charged with murder.

The wilderness has often attracted men of violence and those wishing to flee their crimes. Such individuals are stock characters of many Westerns and brutal tales of the wild America of our past. Yet, these stories are often based on reality, and both Van Buren and Kimzey stand as examples of that more brutal age when revenge and crime were the fundamental law of the land. While technically, the case remains unsolved, and Kimzey could never be brought to trial for the slaughter, some measure of justice was seen to be done as he remained confined until his old age. If he was involved, however, Van Buren never faced that same justice. The murders at Lava Lake are perhaps then the last vicious example of a United States letting go of the chaos of its infancy and giving way to the general rule of law. They were one of the last acts from an era of unaccountability, a ghost of the past laying bloody in the Oregon wilderness.