Dying Without a Cause: The Murder of Sal Mineo

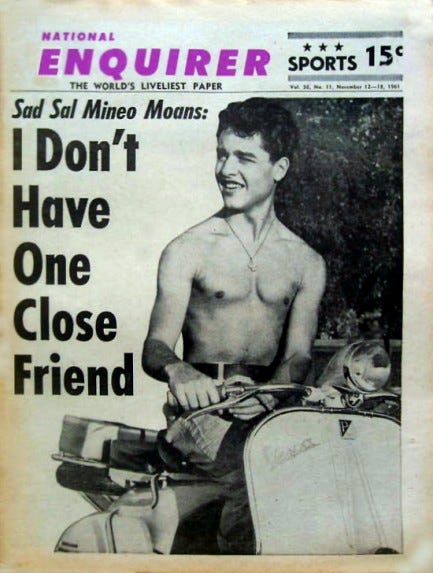

Once one of Hollywood’s brightest prospects, Sal Mineo’s life descended into drugs, sex and loneliness. Police believed his murder had to be connected

Hollywood is the place where dreams are made and broken. For every lifelong megastar, hundreds fail to make it or end up taking bit parts just to get by. Some end up saddled with debt, others with drug issues, or the other numerous problems underneath the movie lifestyle’s glitz and glamour.

Through the 1950s to 1970s, Hollywood underwent an immense change from the conservatism of the 1950s and the era of the infamous blacklist to the liberalism of the 1970s. Cocaine, alcohol, and both straight and gay sex were to be found in abundance. Some would lament the passing of the old ways, while others become known as the life and soul of the Hollywood party, forging a dubious kind of legend.

One such actor was Sal Mineo, who offset his loneliness with many acquaintances, hangars on, and lovers. A child star, Mineo successfully traversed the social changes in Tinseltown while failing to maintain the promise of his teenage career. When he was brutally murdered in 1976, police immediately suspected this hedonistic lifestyle had to be responsible. The truth would be that the sheltered Hollywood had collided with the more violent side of L.A. in the most tragic way.

Mineo was born to working-class roots in New York. He was of Sicilian heritage, with his father being born in Italy. The second generation of the Mineo family were actors, with his sister and brothers all being actors and Sal being enrolled at acting and dancing school from childhood.

He made his stage debut at the age of just twelve and got a break early when he starred alongside the great Yul Brynner in the stage version of The King and I. Brynner acted as a mentor throughout the production, offering advice and help to the rising child star. An aspiring star could barely have asked for a better tutor. He would make several television appearances before his first film role in 1955’s Six Bridges To Cross, beating the young Clint Eastwood to the part of young Jerry and following up with The Private War of Major Benson, where he starred alongside Charlton Heston.

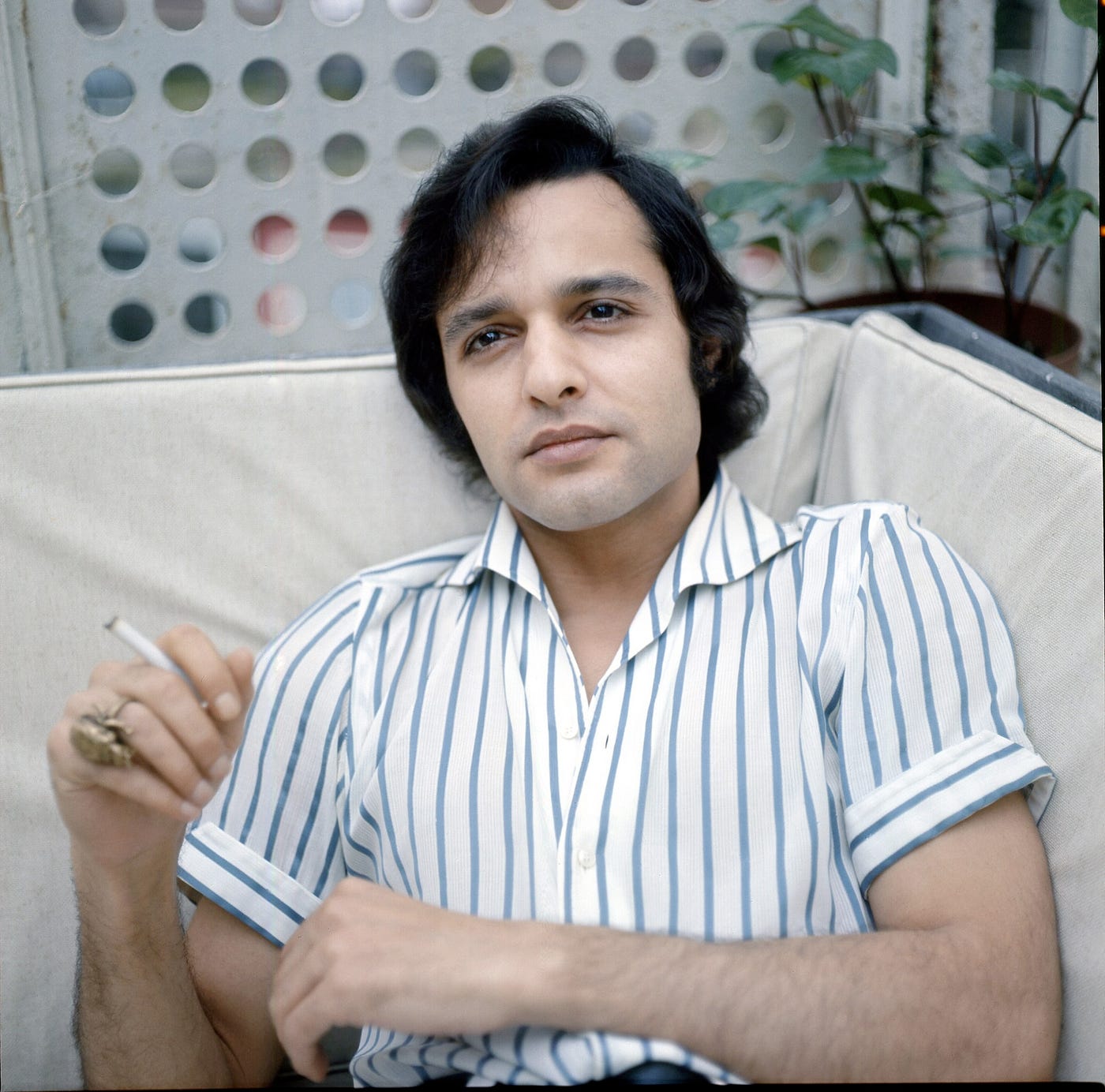

At just seventeen, Mineo was a name to be watched in Hollywood. When he starred alongside James Dean in the classic Rebel Without a Cause as John Crawford, he became one of the youngest nominees in the history of the Academy Awards, being nominated for Best Supporting Actor. Suddenly Mineo was a star, and he was seen with some of the most beautiful women in both Hollywood and New York, receiving thousands of fan letters from teenage girls.

However, his status as a teen idol meant that he was quickly typecast in roles that echoed Rebel Without a Cause. Yet, his star didn’t diminish, and by the end of the 1950s, he was one of the biggest names in Hollywood and much in demand. Attempting to go against the typecasting, Mineo took roles such as a Native American in 1956’s Tonka and as a Mexican boy killed during the Second World War in Giant from the same year.

1960 was a critical year for Mineo; he met the English actress Jill Haworth on the set of Exodus, an epic but controversial tale that centered around the foundation of the state of Israel. Mineo’s performance as the Jewish Holocaust survivor Dov Landau alongside Paul Newman and Ralph Richardson won him his second Best Supporting Nomination at the Oscars and a Golden Globe for the same category, beating Peter Ustinov for Spartacus.

However, this was to be the high point of his career. Now in his early 20s, Mineo was considered too old for the teenage heart-throb parts. Despite his relationship with Haworth, word had spread that he was a closeted homosexual, some even gossiping he had been lovers with James Dean. The rumors made him unsuitable for leading roles in the Hollywood of the day. One minute he was auditioning for Lawrence of Arabia, and next, the offers dried up entirely.

There is much debate around whether Mineo’s relationship with Haworth was genuine or she was a “beard” to hide his actual sexual orientation. Mineo was certainly gay and, in his later life, seemingly exclusively so. Yet, he had been engaged to the actress at one point, Haworth ending it when she caught him having sex with a man. Despite the belief that Mineo merely used Haworth to hide himself, it seems that he was indeed in love with the actress, the two remaining friends until his death. In a 1972 interview, Mineo would say he was bisexual, having been in a relationship with the actor Courtney Burr III for six years.

Speaking with Boze Hadleigh for Conversations With My Elders, Mineo would say that “everyone’s supposed to be bi, starting way back with Gary Cooper and on through Brando and Clift and Dean and Newman,” adding “what’s wrong with being bi? Maybe most people are, deep down. .. But anyhow, the rumor about me, from what I hear, was usually that I’m gay. Where, like, with Monty Clift or Brando, the rumor was that they’re bi.”

Throughout the 1960s, Mineo remained active as an actor, but his roles were a far cry from the significant pictures of his youth. He starred in The Greatest Story Ever Told (1965), yet his leading role in 1965’s Who Killed Teddy Bear as insane stalker Lawrence Sherman did not help matters. Although his name was at the top of the bill and critics lavished praise on his performance, it resulted in a new wave of typecasting, Mineo now being seen as a perfect villain.

By the end of the 1960s, attitudes toward homosexuality were beginning to change, with Illinois being the first to decriminalize same-sex sexual intercourse in 1962. However, it wouldn’t be until the 1970s that more states followed suit, firstly Connecticut, Idaho, and Utah in 1971, with partial repeals of the ban coming in Alaska. Colorado and Oregon would follow, and as pressure mounted across the United States, Mineo felt more comfortable being who he was in public.

In 1969, Mineo would star and direct a stage adaptation of John Herbert’s Fortune and Men’s Eyes, a gay-themed play exploring a young man’s experience in prison. The then-unknown Don Johnson took the lead role with Michael Greer playing alongside him as his cellmate. While the play received rave reviews, some were critical of the production featuring scenes that Herbert had not approved, while others criticized a sexually violent rape scene.

Mineo’s last movie role would come under heavy makeup in Escape from the Planet of the Apes (1971), where he played Dr. Milo. There would be other roles on stage and television, including a Harry O T.V. movie alongside guest roles on Columbo, Hawaii Five-O, Mission Impossible, and S.W.A.T. Still, as the 1970s wore on, it appeared that his career was on an irreparable slide into relatively minor guest roles.

That was until 1976. Mineo won the role of a failing actor and bisexual burglar, Vito, in the Tony Award-winning play P.S. Your Cat is Dead by James Kirkwood Jr., staged in San Francisco after a successful run on Broadway. The actor received massive publicity for the role and rave reviews, his career suddenly being revitalized. Mineo moved to Los Angeles along with the play. With its liberal drugs, gay scene, and colorful characters, it was a city that Mineo had always loved and fit right into.

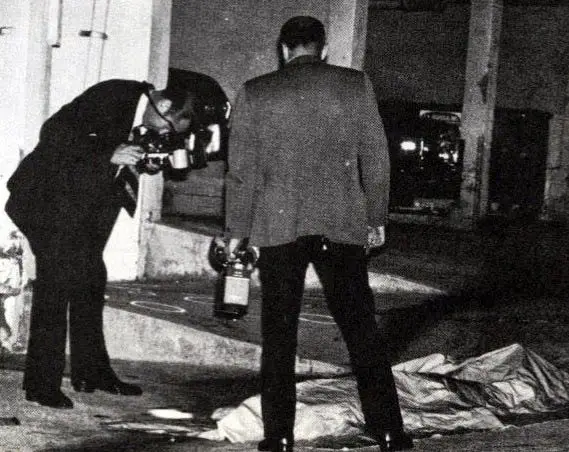

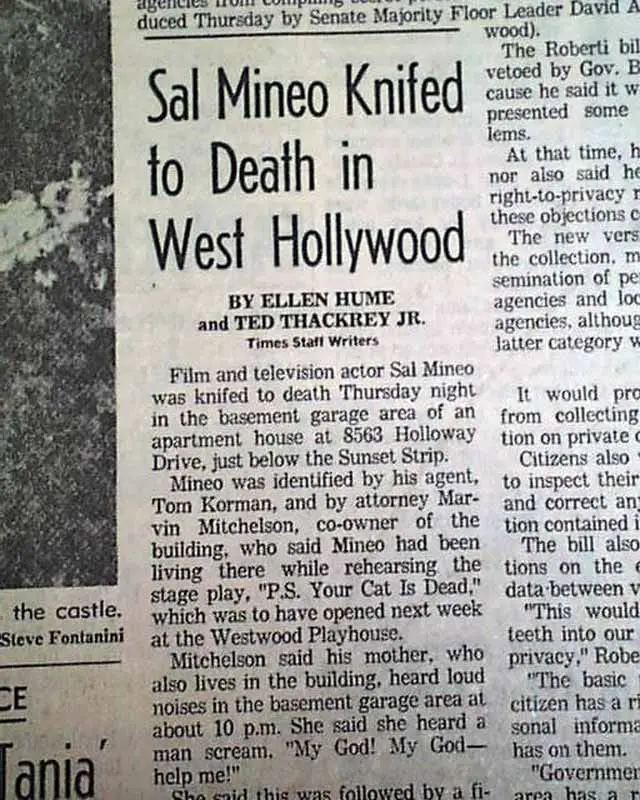

It was the night of February 12, 1976, and Mineo was returning to his Park Wellington Towers apartment in West Hollywood from rehearsals. He parked his car in an alleyway carport underneath his home. Seconds later, witnesses in the area heard a scream of “Oh, God. Someone, please help me!”

Around 9:45 pm, police received the call from neighbors, arriving to find two civilians giving fruitless aid to Mineo. Wearing jeans, a jacket, and a blue shirt with red and white flowers, the actor had been stabbed in the heart, an enormous pool of blood surrounding his body. He was pronounced dead ten minutes later at the age of 37. When neighbors heard the commotion and news that Mineo had been killed, many approached the crime scene. Their footprints were even in the pool of blood.

Speaking with Boy Culture in 2011, Courtney Burr would say that “Even though the apartment was in my name here in L.A. — I had signed the lease because Sal’s financial situation was dubious — when the murder took place, they cordoned it off, and they wouldn’t let me in.”

Sealing off the scene, police set to work and began taking statements. Steve Gustafson, a neighbor, and Scott Hughes, a Wellington Towers security man, reported seeing a figure fleeing from the scene. They described him as young, white, around 5’10” and slender with long hair. Other witnesses said they heard a car engine immediately after the screams.

The press caught wind of the killing quickly, breaking the news that the two-time Oscar nominee had been killed in Hollywood. Speculation immediately ran rampant, with many speculating over Mineo’s sexuality playing a role, despite no evidence to suggest anything of the sort. One witness told police that there were always “young men in and out” of his apartment and “they were gay, he was gay.”

What was ascertained was that Mineo took cocaine and was struggling for money at the time, slowly recovering his finances after accumulating large debts in previous years. His social circle was large, with most of his friends also being gay and many of them being of a dubious nature. His friend Kristine Clark told investigators that “I know that Sal knows a lot of people. And not all of them are what you would call fine, upstanding citizens.”

Further investigation of Mineo’s private life revealed allegations that would have been headline news in this era yet seemingly went almost without comment in the 1970s. The actor liked a particular type of lover, namely small young men who were of low intelligence. His conquests were between 14 and 25, enjoying playing both physical and mind games, all designed to frustrate the other individual.

Police trawled the local gay bars and began to contact those listed in his address book, desperately seeking a lead in the case, everything coming back negative. Everyone seemed to know Mineo or knew a friend who knew a friend who knew Mineo. They’d had sex together, or taken drugs, or simply hung out at his apartment. While Mineo had an address book full of A-list names, he seemed both at the same time lonely and more at home amongst the not very fine “upstanding citizens” than he did the glitz and glamor of the red carpet.

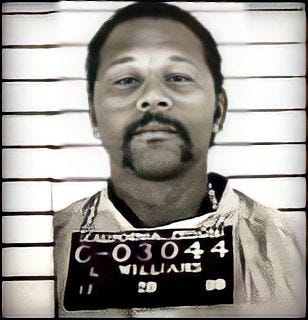

It was over a year before police had their first strong suspect, pizza deliveryman Lionel Williams, a Black man with an afro. It is often the case that police desperate for a result would pull in low-level Black criminals and attempt to pin the crime on them. Here early witness statements state a White man had been seen running from the scene, yet police would come to believe that was a mistake, and the man sighted either had nothing to do with the crime or, given the alley’s darkness, could have been the light-skinned Williams. The latter wore his hair slicked back at the time.

Williams’ then-girlfriend and current wife, Teresa Collins, 19, had contacted the police in April of 1977, stating that Williams had intended to buy a knife on the night in question. Previous experience told her that her boyfriend planned to commit a robbery, having been with him during two previous crimes. That night she stayed at the home they shared with Williams’ mother, and later that evening, Williams returned home, flashing the knife and admitting he’d stabbed somebody. He told Collins that the victim was “a young-looking white dude in Hollywood.”

Collins also reported that a month after the killing, the pair spent time with one of her friends, La Sonya Armstrong. After hearing the dead man’s identity on the radio, Williams boasted to Armstrong that he had killed Sal Mineo. The girl didn’t believe him and Willaims went to retrieve the murder weapon before eventually threatening that he was going to put her “on the street to make me some money.”

Collins was the first genuinely credible witness that police had got in the year-old case, and she readily agreed to a polygraph which she passed. However, there was already an issue developing as the murder weapon that Williams had hidden in his home was no longer available for evidence. The Williams residence was burgled the year before, with the knife being stolen alongside expected items such as a television, radio, and money. However, Collins was more than eager to help investigators and picked out an identical knife that experts concluded had likely been of the type used to kill Mineo.

An A.P.B. was put out for the arrest of Lionel Williams in August of 1976, the suspect’s whereabouts being a mystery, having last been known to be in Michigan. He eventually turned up in Calhoun County, and police began to build their case by interviewing friends and relatives, fellow criminals, and his regular haunts in L.A. In Michigan, police bugged the cells and visiting room, hoping to catch the suspect in a moment of indiscretion.

In July of 1977, such a moment would come. Williams, who had offered nothing that could be used in court, told fellow inmate Philbert Gallard that he stabbed Mineo. The conversation was overheard by a deputy. While the overheard confession was good, would it be enough to put the suspect behind bars without physical evidence? Probably not. But better was soon to transpire, and tips came in that Williams had had an accomplice.

Michael Alley was Williams’ neighbor at the time of the killing, and the tipsters claimed he had been Williams’ driver on the night of the killing. Cutting a deal with the District Attorney, police were authorized to offer Alley immunity if he ratted out Williams. Alley took the deal and revealed that on the night Mineo was murdered, the two had been out drinking and looking for women. Williams took over the driving as Alley fell asleep.

Waking up, Alley soon found his friend pulling into some apartments and leaving the vehicle. From the car, he witnessed Williams briefly talking to somebody before stabbing him. Alley’s statement alongside those of the deputy, Armstrong, and Collins, who even provided bloodstained clothing used during the murder, was deemed enough. Williams was extradited from Michigan in January of 1978.

The January 1979 trial hit a significant roadblock early when Collins invoked her spousal privilege not to testify; however, it made little difference in the end, the verdict being guilty. Williams was sentenced to at least 50 years in prison for the murder of Mineo and ten other robberies. Judge Bonnie Lee Martin of Superior Court said, “The defendant should be committed to state prison for as long as the law allows.” Williams was paroled in 1990 after serving 12 years.

Police initially expected that the killing of Sal Mineo had some connection to his lifestyle. It was almost inconceivable that the drug-taking promiscuous Mineo could not have been a victim of a gay encounter gone wrong. Unfortunately for Mineo, it was simply a case of being in the wrong place at the wrong time and meeting the wrong person, with Lionel Williams determined to acquire money that evening and being willing to deal out violence to ensure it. On the cusp of a career comeback, Mineo will be remembered as a star that burned brightly in the beginning and faded away as prejudice and his lifestyle overcame his immense talent.