Blood on the Snow: The Killing of Elli Immo

With No Weapon, No Motive and No Suspects, Just Who Killed a Young Girl in the Snows of Lapland?

Lapland is seen as a magical place. A place where the snow often falls to a depth of over a meter, and sleds cross picturesque scenes full of fir trees, lights, and Santa Claus for the tourists. It’s a place of rustic charm where nothing evil could ever happen… Sadly, perception and reality are not the same things, and Lapland has just as many issues as anywhere else in the world. The life is hard, and while the cold may seem remarkable to tourists staying a matter of days, the Baltic winds chill locals to the bone. Game of Thrones’ famous warning of “winter is coming” could almost be made for this one area of Finland.

Such was the winter of 1955. In the city of Kemi, southern Lapland, three young women stood freezing in the night air. Maila, Anna Liisa and Elli, more fully Elli Maria Immo. The three had looked around the sights and done a copious amount of window shopping, with the city getting ready for Christmas. It was December 7, and perhaps there were wooden toys for children in the windows, maybe new clothes or food displayed for passing shoppers.

As the clock struck 9pm, Maila told her friends that her feet were freezing and it was time to go home. The three separated, with Maila and Elli, headed one way and Anna Liisa the other. The two friends lived close to each other and, already pitch black, it was safer to walk in pairs. While crime was not an issue, there were numerous dangers, from snow, ice, or even wild animals. However, there was something far more dangerous than a wolf stalking its prey in Kemi that night.

Elli Immo was born on August 10, 1935 in Alatornio. Her father was a police officer there, and after his unexpected death, the family moved to Kemi. She enjoyed her time in the 25,000 strong city, significant for the area, being friendly, cheerful, and sociable. The family lived in the suburbs, and in the fall of 1954, Elli enrolled at the Kemi School of Economics alongside having a part-time job as a business assistant in the wallpaper and paint trade. She was a typical student that we would recognize today, being more concerned with her life in the city center, going dancing, watching movies, and spending time with friends at cafes. She was having fun.

On December 6, Elli had enjoyed an entertaining night when she traveled around 5 miles to Lautiosaari. An early Christmas party was underway at the Karelian Society House, and Elli had tickets. There was dancing and plenty of men. Elli had attracted the particular attention of one man, yet it didn’t seem unwelcome as the following day she expressed how much fun she’d had to her friends.

The morning of December 7, however, had been unusual for her. Elli hadn’t seemed her usual jovial self, and witnesses described her as sullen or even angry. It transpired that she had quarreled with another student over photographs. Yet, it wasn’t as trivial as it initially sounded. A boy at the Kemi School of Economics was tasked with collecting class photo orders and subscriptions. However, what nobody knew was that the photo studio being used offered a 10% discount for all students. The boy was pocketing the extra money for himself, and Elli exposed the fraud. Brought before the Students’ Union, they decided the extra money should go to them. The boy was outraged and had written Elli a letter that police later described as “malicious.”

However, all was forgotten by the evening, and she set out on the town with Maila and Anna Liisa. They headed to the three cinemas in the city and tried to find a movie; however, Elli and Anna Liisa had already seen what Maila wanted to watch.

Instead, they went to the Mokka-Tuva café and then Valio Bar before heading home. As Malia and Elli set off, two young teenage boys asked to escort them but were turned down. Pulling their beanie hats tight to keep out the cold, the two went along the Lapintie road. Elli had crocheted her hat herself and was said to be very proud of it. Arriving at Elli’s house, Malia asked if she minded walking a little way with her toward her home, there being no street lights at all. Elli didn’t mind and joined her friend for around 250 meters of the journey. The two parted around 9:30pm, and Elli began the short distance back home. She would never make it.

Before midnight, Elli’s mother returned home from work, walking the same path Elli would have walked. The front door was unlocked, but this was usual, with fear of crime being almost nonexistent. Elli’s three brothers were already asleep, and the rooms were hot, Elli having warmed the house as usual when she had got home from classes. The girl’s bags and books were still present on the living room floor, and her mother deduced she must have done some study before heading out. Her absence wasn’t particularly worrying as her daughter had been known to spend the night at Anna-Liisa’s before. Though, she usually took some bedding with her…

At 12:50pm the following day, a schoolboy discovered Elli Immo’s body lying on her stomach next to the path from Lapintie to Ristikanka, where she lived. She was just 30 meters from home. She was wearing the same dark green jacket and winter boots as the night before, and her beloved crocheted grey beanie had fallen beside her. She was covered in snow. Her killer had struck brutally, stabbing her several time in the right side of the neck and behind the ear, the cause of death. Some of the snow had been placed there by her killer, covering her face and upper body. Despite the corpse laying on a public path, including the one that Elli’s own mother had walked, the body had been somehow undiscovered.

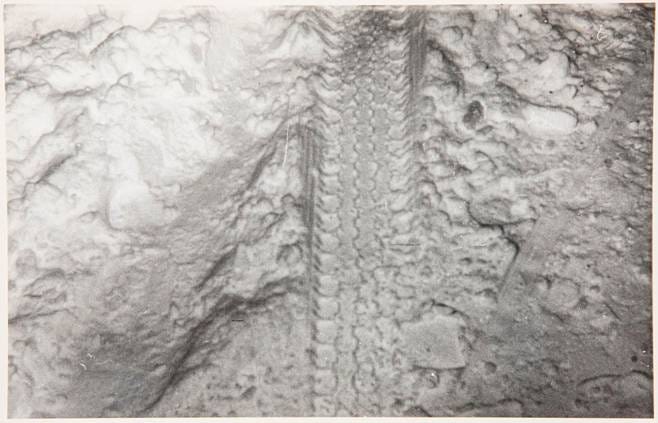

Investigating the scene, police noted both footprints from a large man’s ski boot and bicycle tracks in the snow. Next to the body was found the sheath for a Mora knife. Morakniv knives have been crafted in Östnor, Sweden, for over a century. They were standard for many craftsmen, once being handmade by generation after generation. Alongside crafts, they are frequently used for the likes of camping and bushcraft. Owning one in Lapland would not be unusual. The murder weapon was never found by police, though a knife was handed in after it was found on a bus, police being unable to ascertain whether it was connected to the killing.

Police carried out extensive inquiries and searches in Kemi, with 60 people quickly questioned, including Maila, who said she had gone home and listened to the radio. Police checked with the broadcaster to ensure that the programs began when she said they did. In today’s age of ready information, it seems rather strange that such a thing could be a legitimate alibi. Still, we must remember the era and the community’s isolation, where radio schedules were unavailable and frequently prone to interruption. Speaking with a 22-year-old who lodged at Elli’s home meanwhile, the young woman recanted that the previous evening she’d heard a loud shout followed by a quieter exclamation between 9.45pm and 9:50pm. It had sounded like somebody in need.

The photo scam boy was questioned, but an alibi placed him at home all night, with family testifying on his behalf.

Elli was neither robbed nor sexually assaulted, leading police to theorize she had either been the victim of a lunatic or her father’s police work had been the motive, someone from his past seeking revenge. Her father was straight-laced and strict, formerly working the western border and stopping smuggling. Though why somebody might target Elli when her father was long dead was never made clear, and the sense that police were struggling for either a motive or a suspect was apparent.

A truck driver was arrested, with his clothes being sent for analysis. Although oily from his profession, no concrete evidence was found against him, and he was released. Clothes were taken from others, homes searched, knives analyzed. Witnesses reported a strange man who jumped off a train mid-journey; another said a man was conducting his own personal inquiry. The police file was full of false reports and rumors.

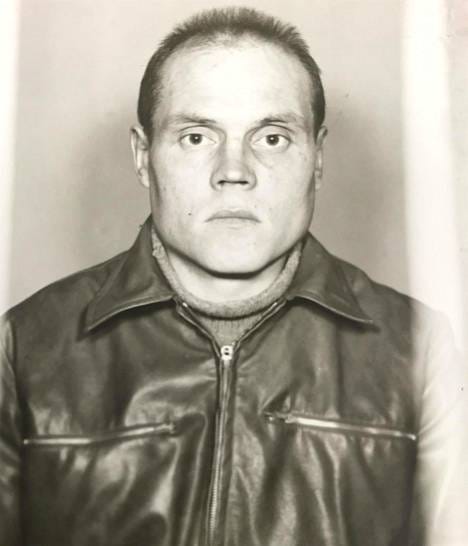

The only suspect who has ever been named as having been questioned is Runar Holmström, the man brought to trial for the double murder of two young women during the infamous Tulilahti campsite murders.

Holmström, a petty thief, stood accused of the stabbing and bludgeoning of Riitta Pakkanen, 23, and Eine Nyyssönen, 21, having admitted to stalking the girls on his moped. The bodies were dragged from their tent in the middle of the night in July 1959, being buried in a grave at a nearby swamp. However, there was significant evidence that Holmström was innocent, a belief publicly stated by both the prosecution and judge after his suicide in 1961.

However, on February 22, 1960, Central Criminal Police interrogated Holmström over the killing of Elli Immo. He denied the murder and said that he was at home in Munsala through the entire winter of 1955–1956. However, in many respects, he was evasive. When asked where he acquired the Mora knife he carried, Holmström could only say he had received it “somehow” in September 1959, yet couldn’t explain where. The sheath that he put the knife in wasn’t the original one that came with it, and again, Holmström couldn’t remember what happened to the original. When asked whether anyone except those in his household could verify he’d been at home, he said that guests had come over but couldn’t name who. He refused to give a handwriting sample, even though that would have little bearing on the case.

Eventually, nothing came of the investigation, and the case went cold. However, in 1972, two of the original three Kemi Police Department officers on the matter, Juho Tepponen, and Pekka Vitikka, stated that the affair should be reinvestigated, saying that the perpetrators had been protected during the original 1955 investigation. However, despite their statements, they never made a formal request for an investigation into the allegation. Some thought that a police officer had been involved in the killing.

Anyone who has read our Nordic Noir book will know who’s coming next: Hans Assmann.

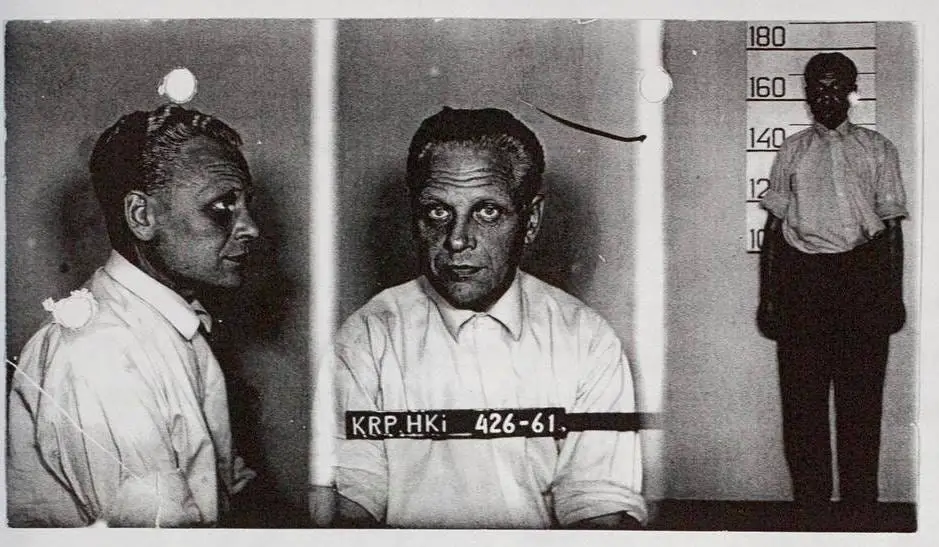

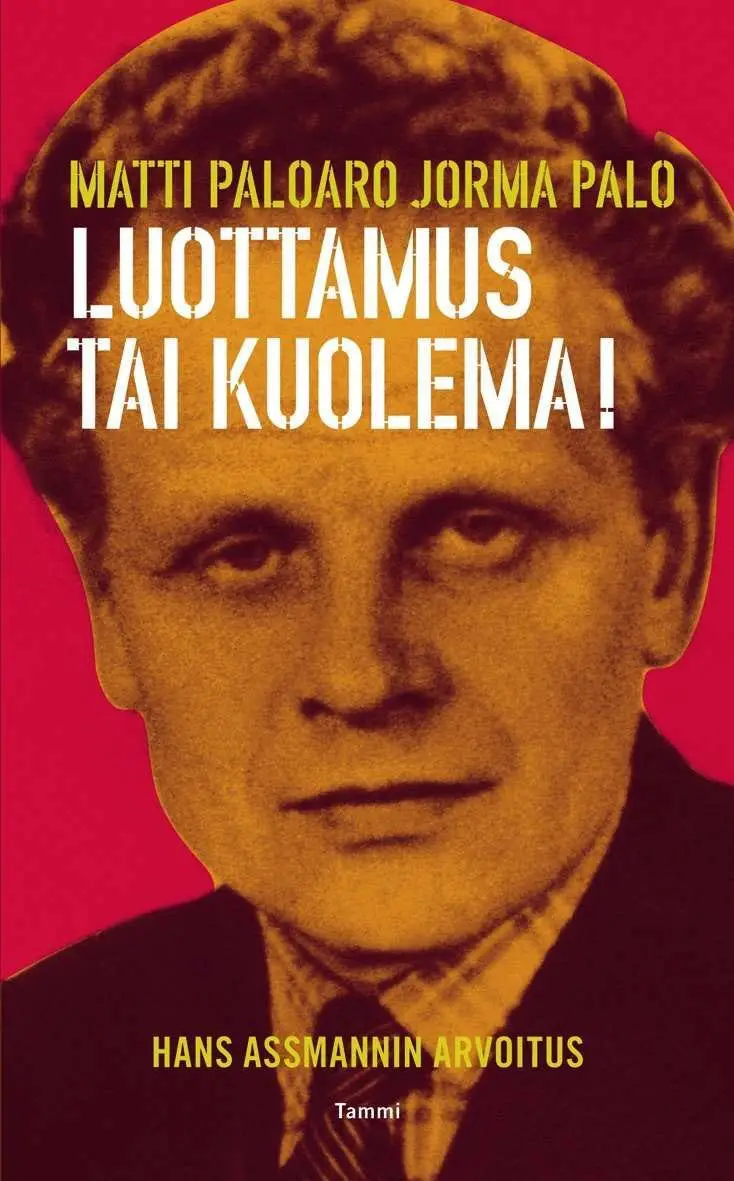

Hans Assmann is infused in Finnish true crime circles and, in many respects, almost a boogeyman. He has been linked to numerous crimes, and in many ways, the evidence is usually “found” by writers and enthusiasts to ensure he is included. The only crime he was ever linked with at the time was the Lake Bodom affair, and he was quickly dismissed from inquiries after providing a watertight alibi. That didn’t stop a doctor who treated him the night after those killings from releasing a series of sensational books that turned him into a one-man crime wave.

Assmann was by no means a nice man, being an alcoholic and once beating his own wife in public, finding himself under arrest. However, it’s a long way from that to being responsible for dozens of murders. Assmann, however, seemed to enjoy the infamy and, in 1997, on his deathbed, invited then editor of the Alibi true crime magazine, Matti Paloaro, to hear his life story.

Assmann claimed to have been a member of the SS and a guard at Auschwitz before turning on his German countrymen and joining the Soviet KGB. After that, he strung out a long series of hints to suggest he may have been involved in a whole range of unsolved crimes, including the murder of Kyllikki Saari and more. While his claims may occasionally have a ring of truth, most of what he said was complete and utter fantasy, and the Finnish police consider the books written about him to be little more than fiction.

Key to the claims of the books and belief in Assmann as a uber-villain are the statements of his ex-wife Vieno Assmann. Vieno has been happy to provide “evidence” that her ex-husband was always in the area when a murder was committed. She equally claimed that he had incriminated himself in other ways, such as leaving the house with a shovel after the death of Kyllikki Saari. For a supposed KGB agent, he seemed very sloppy.

In the Elli Immo case, the theory has been proposed that Assmann was a man Elli danced with at the party on the night before her death, with Vieno Assmann delighted to claim that her husband was in Kemi that same evening. It’s worth noting that it’s been established that Assmann was never in the SS or at Auschwitz; he was in the Luftwaffe. Likewise, he was in Germany during some of the killings attributed to him, and Sweden for others.

Hans Assmann may be the exciting supervillain everyone would like to have committed the killings, yet the reality is that he simply isn’t. It makes a great story, yet also it allows us to detach ourselves from reality. It is comforting to think that such senseless and brutal murder is the work of shadowy forces such as the KGB or an ex-Nazi; they are detached from us; they are not our friends or neighbors. The reality is, that’s exactly who most murderers are, and all the killings attributed to Assmann were truthfully brutal, vicious, and sordid snapshots of our own human nature, not the work of a pantomime villain.

The killing of Elli Immo is one of those tragic crimes with no motive, no suspect, and very little chance of a resolution. Police were at a loss in 1955, and today the case is long since cold. The hope that somebody in old age might yet be brought to justice is very slim. While Runar Holmström may have been alarming in some of his statements, there was nothing to really link him with the crime, and Hans Assmann should be dismissed as the fiction that the police claim his crimes to be. With all suspects eliminated, it seems justice for Elli Immo will remain forever elusive.