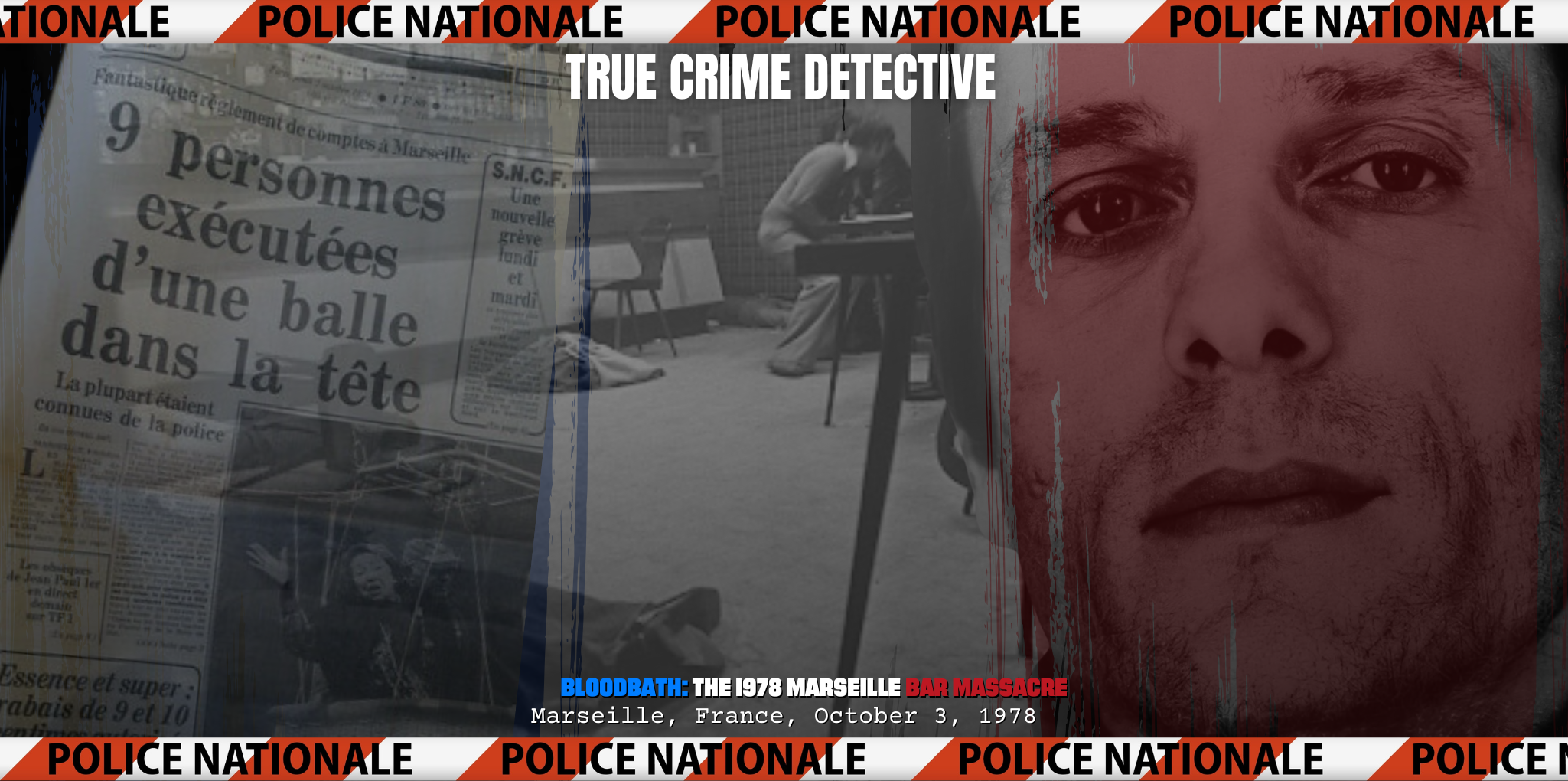

Bloodbath: The 1978 Marseille Bar Massacre

France has long been a country of intense political passions and a violent criminal underworld that goes unnoticed by international observers. To those abroad, France remains a country of fine dining, high fashion, and charm. Yet, the country also has one of the highest murder rates in all of Europe, with organized crime, or le milieu (“the underworld”) being a particular issue. Known as the French Mob, nowhere is the scourge of les beaux voyous (“the goodfellas”) felt more keenly than Marseille, arguably the centre of organized crime in the country. That centre would be secured on October 3, 1978, when three armed men walked into a bar in the city. Minutes later, 10 people had been shot dead in an unsolved crime that some call the French St. Valentine’s Day Massacre.

Marseille has long been a city of contrasts. Rich and poor neighbourhoods sit directly alongside each other, and the city has been a centre of immigration throughout its history, thanks to its prominent nature on the Mediterranean. Algerians, Tunisians, and Moroccans live side-by-side with Italians, Poles, and Turks, creating one of Europe’s great melting pots that is mostly devoid of Paris’ violence. However, an economic downturn in the 1960s resulted in an exodus. The poor were left to continue their life in Marseille, allowing the mafia to exploit those in need to their fullest extent. They moved into prominent positions and, for a time, effectively ran France’s ancient “Phocean City.”

It was just before 8pm that a dozen fresh customers entered the Tuerie du bar du Téléphone at 8 boulevard du Commandant Finat-Duclos in Marseille. Despite the pleasure of fresh customers, owner André Léoni was likely slightly irritated as he was just getting ready to call last orders and close-up for the night. His wife, Nicole, was duly sent to fetch wine. It would be the last time she saw her husband alive as around 8:10pm, three hooded men entered the bar downstairs brandishing pistols and a sawn-off shotgun.

The gunfire echoed through the night air of the boulevard du Commandant, the killers systematically gunning down every single person left inside Le Téléphone. Not a single bullet went astray. Not a broken glass, not a broken window. With the patrons downed, the crew went from body to body, firing the final coup de grâce into their heads. Nine people were dead at the scene, and a tenth died in hospital. The entire slaughter took just four minutes. Commander Christian Maraninchi, an inspector with the Marseille police, said, “There was so much blood on the ground that it was up to the ankles.”

The dead were Alain Armanian, Guy Audemard, Fernand Bourrelly, Henri Ciron, Francis Fernandez, Noël Kokos, Jean-Claude Quercia, Paul Straboni, Marcel Touchard, and André Léoni.

The killers escaped on foot down the Boulevard Finat-Duclos, with the police immediately alerted by eyewitnesses in the busy metropolitan area. The only two surviving witnesses were Nicole Léoni, who had seen little, and Jean Kokos, Noël Kokos’ brother, who managed to escape the carnage by hiding in the toilets.

The police’s attention was immediately drawn to Marseille’s criminal underworld, seeing the massacre as the culmination of a turf war that had already claimed 26 victims over the past eighteen months. The victims in the bar were between the ages of 20 and 27. Four were known to police, and two had just been released from prison.

While Marseille, and France in general, had become used to violent crime, the slaughter at Le Téléphone was seen as a step too far, and the Director of Criminal Affairs at the French Ministry of the Interior, Honoré Gévaudan, took personal charge of the investigation. Eyes turned toward Gaetano “Tany” Zampa and Jacques Imbert, better known as “Jack le Mat,” Marseille’s two most prominent godfathers.

Zampa and Le Mat were at war. Both once members of the same gang led by Antonie Guerini, the crew had split into rival factions when Guerini was arrested in the early 1970s, both vying for control of racketeering and casinos on the French Riviera. One of those groups was led by Zampa and the other by Le Mat. By 1977, “Tany Z” was openly attempting to kill his rival, and Le Mat took his terrible revenge, arranging a series of killings designed to take out Zampa’s best gunmen and assassins. Interestingly, one of those killed at Le Téléphone was known to be a gunman for Zampa, Noël Kokos, whose brother, Jean, managed to escape the bar. Jean Kokos himself would be shot just a few years after the massacre in Marseille.

Known as “the emperor of the night” or “the big one” due to his immense height, Zampa had a legendary reputation. His father was a known hoodlum whose criminal career stretched back to the 1930s under the Corsican Paul Carbone and the French-Italian François Spirito. By the end of the Second World War, he had joined with the Guérini brothers, arguably the most influential criminal enterprise in Marseille during the immediate post-war period. Tany Zampa was, therefore, a prince of crime in the city.

Zampas’ power is best told by an anecdote from the days that the Communist Party ran city hall. Gaston Defferre, a more moderate socialist, had his eyes on regaining the position of mayor, and faced with an intense demonstration by the communists, he unwisely tasked his 20-year-old bodyguard with clearing the crowd. It was Zampa, and he was armed with a submachine gun. The crowd duly dispersed, and the gangster told the future mayor of Marseille, “You are in debt with me. I don’t want you to forget it. Because the most powerful man in Marseille is not you, it’s me.”

Le Mat meanwhile had a far more respectable upbringing, his father working in the aeronautics industry. Indeed, he may never have fallen into the world of crime at all had it not been for a stepfather who had enraged the young man enough to punch him in a bar. Sentenced to a harsh five years in prison, Le Mat fell in with a tough crowd and began to see violence as the way forward. After his release, he eventually joined the Three Ducks Gang, mainly made up of Italians. Through this membership, he first came into contact with Tany Zampa, and the two became fast friends.

The life of Le Mat has movie potential written all over it, being an expert in robbery and particularly noted as a getaway driver. He worked as a stuntman and raced cars at the Old Port quays, showing off his skills at the Place de la Concorde in Paris, being noted as an infamous ladies’ man. He owned his own stud stable, and some believe he even secretly starred as an uncredited extra in the French-German film Borsalino and Co. However, this playboy image covered a man willing to torture, maim and kill to advance his criminal career, and he quietly built his own crew of 20 men. While he officially followed Zampa’s orders after his friend rose to the top, Le Mat remained independent, and his strength was growing.

Le Mat would eventually make an alliance with the Gypsy Mafia, and Zampa could tolerate his machinations no longer. On February 1, 1977, three masked men opened fire on Le Mat in the parking lot at his residence in Les Trois Caravelles, Cassis, leaving the gangster for dead. Standing over his dying former friend, Zampa was reported to have said, “A bitch like this is not worth the coup de grâce; let him die like a dog.” Only, Le Mat didn’t die, and despite losing the use of his hand and being blinded in one eye, he survived. His quest for vengeance would set Marseille aflame in what police called the city’s “Hundred Years War.”

However, despite many seeing the links between the Zampa/Le Mat war and the Marseille bar massacre as evident, police were unable to conclusively make any connection between the majority of the victims and organized crime. Many observers said that it was unlikely for either party to find such collateral damage as acceptable if the only target had been the one man linked to Zampa with both gangs having a code that no innocents were to be harmed, it being considered sacrosanct. Indeed, on one occasion, Zampa had refused to kill a mortal rival as the target’s mother had been with him.

While this code may seem incredulous, the fact remains that there was seemingly no reason for anyone else in the bar to have been executed, and Honoré Gévaudan was one of the primary voices discounting the involvement of either gang.

However, the code would not have been broken if those killed “had to die,” and there were some reports that a brave patron had grabbed the balaclava of one of the assailants, unmasking him and forcing the attackers to upgrade their plan from a single assassination into the elimination of all witnesses. Equally, the testimony of Nicole Léoni said that she had come face to face with one of the attackers and been spared, perhaps because of the creed.

With little progress being made, the famed Judge Pierre Michel was put in charge of the case as examining magistrate. Michel was instrumental in dismantling the infamous “French connection” drugs network, and his team had closed countless other drug labs and criminal enterprises. Michel’s investigations discovered that gangsters involved in the networks had been forced to change their schemes and had moved into counterfeit money. In 1978, alongside Commissioner Châtelain, Director of Urban Security, Judge Michel came to believe that these networks of counterfeiters were behind the massacre in Marseille. Talk soon surfaced that a suitcase of counterfeit banknotes had passed through the Le Téléphone, everyone in the bar that night had been involved, and Nicole Léoni knew far more than she was letting on.

However, just as the net seemed to be tightening, the case would be blown away. On October 21, 1981, two helmeted men on motorcycles drew alongside Judge Michel’s own motorbike on Boulevard Michelet. They opened fire with 9mm pistols, killing the judge instantly. While the killing is believed to have been a revenge attack carried out by two drug traffickers that Michel had put in jail, his death effectively ended investigations into the Marseille bar massacre.

There were other theories in the case. The police favoured that it was a dispute between rival pimps; others saw the hand of the Civic Action Service (SAC) in the killings, a violent militia dedicated to defending the ideals of Charles de Gaulle. In July of 1981, the SAC would massacre an entire family as part of internal rivalries in Marseille in killings known as the “Auriol massacre.” Yet, none of the other leads went anywhere, and the case was cold.

Sitting at the centre of the violent “Hundred Years War” in Marseille between Zampa and Le Mat, it seems unlikely that the two rival Milieu gangs weren’t involved at some level or at least had knowledge of who was responsible. Likely taking place as part of the tragic fallout from the fall of the French connection, the spectre of counterfeit money and shady dealings in the backroom of bars lingers large, and it’s possible that some of those at Le Téléphone got into an affair way out of their league. However, with 10 men dead, nobody was likely to talk, and the Marseille bar massacre remains unsolved.